|

) is the fifth of Jupiter's

known satellites and the third largest;

it is the innermost of the Galilean moons.

Io is slightly larger than Earth's Moon.

) is the fifth of Jupiter's

known satellites and the third largest;

it is the innermost of the Galilean moons.

Io is slightly larger than Earth's Moon.

orbit: 422,000 km from Jupiter

diameter: 3630 km

mass: 8.93e22 kg

The pronunciation "EE oh" is also acceptable.

Io was a maiden who was loved by Zeus (Jupiter) and transformed into a heifer in a vain attempt to hide her from the jealous Hera.

Discovered by Galileo and Marius in 1610.

In contrast to most of the moons in the outer solar system, Io and Europa may be somewhat similar in bulk composition to the terrestrial planets, primarily composed of molten silicate rock. Recent data from Galileo indicates that Io has a core of iron (perhaps mixed with iron sulfide) with a radius of at least 900 km.

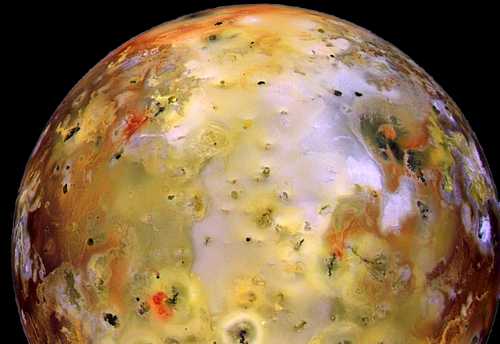

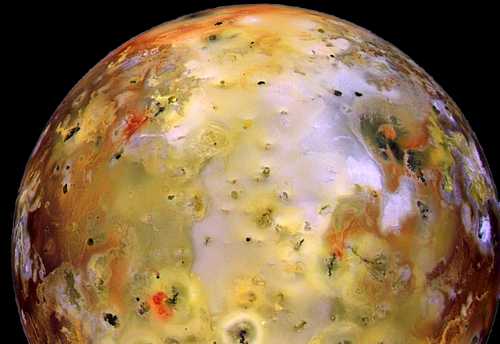

Io's surface is radically different from any other body in the solar system.

It came as a very big surprise to the

Voyager

scientists on the first encounter. They had expected to see impact craters

like those on the other terrestrial bodies and from their number per

unit area to estimate

the age of Io's surface. But there are very few, if any, impact craters on Io (left).

Therefore, the surface is very young.

Io's surface is radically different from any other body in the solar system.

It came as a very big surprise to the

Voyager

scientists on the first encounter. They had expected to see impact craters

like those on the other terrestrial bodies and from their number per

unit area to estimate

the age of Io's surface. But there are very few, if any, impact craters on Io (left).

Therefore, the surface is very young.

Instead of craters, Voyager 1 found hundreds of volcanic

calderas.

Some of the volcanoes are active! Striking photos of actual eruptions

with plumes 300 km high were

sent back by both Voyagers (right) and by Galileo (bottom left image on this page)

This may have been the most important single

discovery of the Voyager missions; it was the first real proof that the

interiors of other "terrestrial" bodies are actually hot and active.

The material erupting from Io's vents appears to be some form of sulfur or

sulfur dioxide. The volcanic eruptions change rapidly. In just four months

between the arrivals of Voyager 1

and Voyager 2 some of them stopped

and others started up. The deposits surrounding the vents also changed

visibly.

Instead of craters, Voyager 1 found hundreds of volcanic

calderas.

Some of the volcanoes are active! Striking photos of actual eruptions

with plumes 300 km high were

sent back by both Voyagers (right) and by Galileo (bottom left image on this page)

This may have been the most important single

discovery of the Voyager missions; it was the first real proof that the

interiors of other "terrestrial" bodies are actually hot and active.

The material erupting from Io's vents appears to be some form of sulfur or

sulfur dioxide. The volcanic eruptions change rapidly. In just four months

between the arrivals of Voyager 1

and Voyager 2 some of them stopped

and others started up. The deposits surrounding the vents also changed

visibly.

Recent images taken with NASA's Infrared Telescope Facility on Mauna Kea, Hawaii show a new and very large eruption (right). A large new feature near Ra Patera has also been seen by HST. Images from Galileo also show many changes from the time of Voyager's encounter. These observations confirm that Io's surface is very active indeed.

Io has an amazing variety of terrains:

calderas up to several kilometers deep,

lakes of molten sulfur (below right),

mountains which are apparently NOT volcanoes (left),

extensive flows hundreds of kilometers long

of some low viscosity fluid (some form of sulfur?),

and volcanic vents.

Sulfur and its compounds take on a wide range of colors which are

responsible for Io's variegated appearance.

Io has an amazing variety of terrains:

calderas up to several kilometers deep,

lakes of molten sulfur (below right),

mountains which are apparently NOT volcanoes (left),

extensive flows hundreds of kilometers long

of some low viscosity fluid (some form of sulfur?),

and volcanic vents.

Sulfur and its compounds take on a wide range of colors which are

responsible for Io's variegated appearance.

Analysis of the Voyager images led scientists to believe that the lava flows on Io's surface were composed mostly of various compounds of molten sulfur. However, subsequent ground-based infra-red studies indicate that they are too hot for liquid sulfur. One current idea is that Io's lavas are molten silicate rock. Recent HST observations indicate that the material may be rich in sodium. Or there may be a variety of different materials in different locations.

Some of the

hottest spots

on Io may reach temperatures as high as 2000 K though the average is much lower,

about 130 K.

These hot spots are the principal mechanism

by which Io loses its heat.

Some of the

hottest spots

on Io may reach temperatures as high as 2000 K though the average is much lower,

about 130 K.

These hot spots are the principal mechanism

by which Io loses its heat.

The energy for all this activity probably derives from tidal interactions between Io, Europa, Ganymede and Jupiter. These three moons are locked into resonant orbits such that Io orbits twice for each orbit of Europa which in turn orbits twice for each orbit of Ganymede. Though Io, like Earth's Moon always faces the same side toward its planet, the effects of Europa and Ganymede cause it to wobble a bit. This wobbling stretches and bends Io by as much as 100 meters (a 100 meter tide!) and generates heat the same way a coat hanger heats up when bent back and forth. (Lacking another body to perturb it, the Moon is not heated by Earth in this way.)

Io also cuts across Jupiter's magnetic field lines, generating an

electric current. Though small compared to the tidal heating, this

current may carry more than 1 trillion watts. It also strips some

material away from Io which forms a torus of intense radiation

around Jupiter. Particles escaping

from this torus are partially responsible for Jupiter's unusually

large magnetosphere.

Io also cuts across Jupiter's magnetic field lines, generating an

electric current. Though small compared to the tidal heating, this

current may carry more than 1 trillion watts. It also strips some

material away from Io which forms a torus of intense radiation

around Jupiter. Particles escaping

from this torus are partially responsible for Jupiter's unusually

large magnetosphere.

Recent data from Galileo indicate that Io may have its own magnetic field as does Ganymede.

Io has a thin atmosphere composed of sulfur dioxide and perhaps some other gases.

Unlike the other Galilean satellites, Io has little or no water. This is probably because Jupiter was hot enough early in the evolution of the solar system to drive off the volatile elements in the vicinity of Io but not so hot to do so farther out.