Chapter 20 : Segmenting The Enterprise For Profit Performance Evaluation

LEARNING OBJECTIVES

After studying this chapter, you should be able to:

1 Examine responsibility centers and state their purpose.

2 Relate responsibility centers and responsibility accounting system design to profit performance evaluation.

3 Segment the profit center's income statement for segment and manager performance evaluation.

4 Identify the relevant profit elements for the add-or-drop decision, and describe how product life cycle analysis and the growth /share matrix are used.

5 Calculate profit performance measures for investment center managers.

6 Discuss Kyocera's amoeba system and new organizational structures in American firms.

INTRODUCTION

An enterprise should continuously strive to develop the organizational structure that most effectively and efficiently uses its resources. As enterprises grow and activities become more complex, some division of responsibility is necessary.

In large organizations, one person or a small group simply will not have enough time or sufficient information to make all the decisions. Thus, many medium to large enterprises divide their organizational structure into responsibility centers and place managers in charge of these centers. Then, a responsibility accounting system measures the performance of these managers against their budgets. Responsibility accounting, when properly used in performance evaluation and coupled with an accepted reward system, holds managers accountable for their actions; that is, the activities they manage and the financial factors they control.

To run their responsibility centers effectively and efficiently, managers need information detailing the results of their decisions. To operate successfully, a responsibility accounting system must provide complete and timely feedback that reports on responsibility center performance, either favorable or unfavorable.

RESPONSIBILITY CENTERS

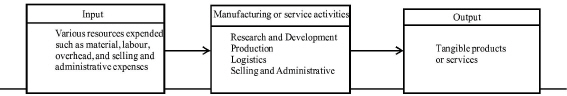

A responsibility center (RC) is a segment of the organization in which a manager is held accountable for a specified set of activities and financial factors, including investment, revenue, and cost decisions. A general model of an RC appears in Exhibit 20-1. Responsibility centers may be created in various ways, but generally the enterprise first divides responsibility by activities. For example:

• Activities related to business functions

• Activities related to products or services

• Activities related to geographic regions

The responsibility accounting system then reports on each RC's financial performance.

|

Activities Related to Business Functions

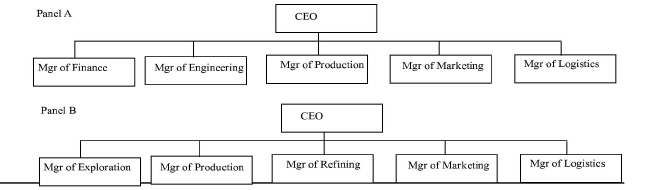

A large number of enterprises divide responsibilities by activities related to business functions. Typical business functions include:

• Finance

• Engineering

• Production

• Marketing

• Logistics

Panel (a) of Exhibit 20-2 presents an organization chart for such an organization, and panel (b) provides a specific example for the business functions of an oil company.

|

LEARNING OBJECTIVE 1

Examine responsibility, centers and state their purpose.

Each manager is responsible for a number of activities related to a particular business function. The chief executive officer (CEO) is responsible for long-range strategic planning and coordinating the activities of all managers. For example, the development of a new product requires coordination among all managers, as described in Chapter 14. Lower-level RCs can also be designated. For example, the manager of logistics may assign a set of responsibilities to a manager of transportation, a manager of warehousing, and so forth. The manager of transportation is responsible for delivering inbound, interfacility, and outbound shipments. The transportation manager is accountable for the delivery of the proper products, on schedule, to the correct destination, and at reasonable cost. At a higher level, the manager of logistics is responsible for coordinating all logistics activities, including transportation.

Activities Related to Product Lines or Services

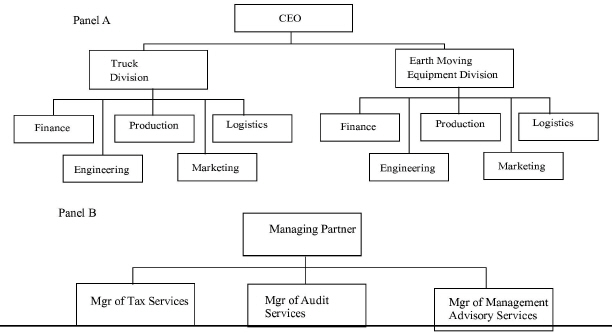

Some organizations set up RCs based on product lines or services. The manager of each product line or service is responsible for all the activities necessary to develop, produce, market, and deliver that product line or service. For example, a manufacturer of trucks and earth-moving equipment would put one manager in charge of trucks and another in charge of the earth-moving equipment, as shown in panel (a) of Exhibit 20-3. The organization chart in panel (b) illustrates the RCs of a public accounting firm.

|

Activities Related to Geographic Regions

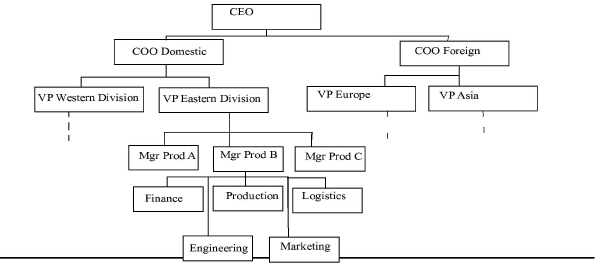

If an organization is dispersed nationally or internationally, RCs may be set up according to geographic regions. For example, an organization may be structured as shown in Exhibit 20-4.

|

In this exhibit, the CEO is responsible for the activities of the organization as a whole, which is his or her RC. The domestic operations and foreign operations are RCs with a chief operating officer (COO) at their helms. Each divisional RC is headed by a vice president. Divisions, in turn, are broken down into lower-level RCs, such as product lines, and then by business function. Alternatively, a division can be broken down into business functions without using product lines as separate RCs Advantages and Disadvantages of Responsibility Centers

In organizations that are divided into RCs, decision-making authority is widely diffused among a number of managers. Managers at levels below top management have authority to make certain major decisions without clearing them first through central headquarters. Creating autonomous RCs is a fundamental tactic in decentralization. Such an arrangement offers both advantages and disadvantages.

THE ADVANTAGES OF DECENTRALIZED RESPONSIBILITY CENTERS. The purported advantages of decentralizing an organization into autonomous RCs include the following:

• Focused decision making. Some enterprises have grown so large that neither top management nor one person can cope efficiently with the volume, breadth, and diversity of the decisions that must be made. Managers of smaller segments possess a better understanding of how the segment operates and what its needs are. Thus, their attention is focused exclusively on the RC to which they are assigned.

• Closer to the action. Because RC managers are closer to the activities and financial factors that they manage, they are on “top of things” and can make more informed decisions.

• Timely decision making. Because RC managers do not have to go through a chain of command to gain approval from top management, they can respond immediately to situations.

• Training ground for managers. Responsibility center managers learn by doing. As they prove their ability to manage smaller segments, they are promoted and given more responsibility.

• Engenders motivation. Being given the responsibility and authority to make their own decisions increases RC managers' incentives to strive for successful outcomes.

• Enhances strategic planning. Because top management is relieved of short-term planning and day-to-day decisions, they can devote more of their time and efforts to long-range strategic planning for the entire enterprise.

• Easier to evaluate managers' performance. Responsibility center managers are given the responsibility and authority to make decisions that will produce certain outcomes. It is, therefore, easier to evaluate them than it is to evaluate managers who have not been assigned well-defined areas of responsibility and authority.

THE DISADVANTAGES OF DECENTRALIZED RESPONSIBILITY CENTERS. The purported disadvantages of RCs include the following:

• Lack of goal congruency. A manager of one RC may make decisions that adversely affect another RC in the organization. The goals of one RC are achieved, but the decision is not congruent with the goals of the organization as a whole. Such dysfunctional decision making can happen in organizations that have highly interdependent RCs.

• Duplication of activities. Dividing an organization into RCs may cause the same activity to be duplicated in each RC. For example, rather than having one information system or accounting department that serves the total organization, each RC may have its own independent LAN. Even worse, a system in one RC may not be compatible with the system in another RC, thus restricting interaction between them.

• Difficulty to compare performance. One reason for decentralizing is that different RCs perform different activities, in different markets, using different resources. Many traditional management accounting systems create upper management reports that directly compare the profitability of divisions without proper regard to whether they are comparable. This “deadly parallel evaluation strategy” can also lead to dysfunctional decisions. For example, would the manager of a McDonald's fast-food restaurant located on the edge of a small town want to be compared against a restaurant located next to a high school or college campus, especially if the managers have no control over the location of their restaurants? If bonuses and profit sharing are based solely on the revenues or profits generated, then the first manager will not compare favorably to the second, even though the first may be doing a better job.

The Role of the Information System in Decentralization

Decentralization requires trade-offs such as the need for LANs to support localized, timely decision making versus centralized information systems to minimize duplication of information processing activities. One of the most serious conflicts from decentralization is the potential sacrifice of goal congruence due to autonomous decision making with RCs. Thus, maximizing employee empowerment and goal congruence become primary goals. So that RCs and their local area networks (LANs) can function cooperatively, an integrated computer-based information system (ICBIS) is needed to link them together. To have decentralized RCs without an ICBIS can actually inhibit effective and efficient local decision making.

A centralized information system is needed to provide divisional information to corporate headquarters. Centralized information about corporate and other RC activities is also needed by RC managers. The ICBIS is more than just a mainframe system with dumb terminals, though. It is an effective combination of PC-based LANs, linked to wide area networks (WANs) (possibly using PCs) and to the corporate headquarter's mainframe.

A modern trend in computer architecture design to support decentralization is downsizing (or “rightsizing”) of the ICBIS. This involves moving away from centralized mainframe systems to client/server networked microcomputers.

|

INSIGHTS & APPLICATIONS Downsizing at Blockbuster Video The interoperable cooperative ICBIS makes optimum use of all resources, assigning the right application to the appropriate level of computer power. Permitting local workstations to prepare transactions and update the database without the use of a mainframe is cost-effective systems design in many companies. Moreover, the PC (or workstation) provides a much friendlier user interface. Interoperable computer architectures enable applications |

to be distributed enterprisewide in an optimal fashion. Such an enterprisewide ICBIS strategy emphasizes decentralized, but cooperative management among all segments of the enterprise. One of Blockbuster's policies is that a movie rented at one store can be returned to any other store. With over 150 outlets, the mainframe video tracking system had to be run every night. Sara Bond, information systems director, downsized the system into a 150-node network of PCs linked through a minicomputer server. Block-buster reported maintenance and support cost savings of approximately $3.2 million annually. Management also claims that productivity has increased from the more accurate and timely tracking of video rentals. |

• Proponents of client/server systems offer many benefits of these system architectures:

• Increased user performance at less cost

• User-friendly interfaces such as graphical displays, no matter where the users are accessing the system (e.g., from another's office, at home, on the RC's shopfloor, or while travelling)

• The ability to distribute centralized information throughout the enterprise so users have real-time access to needed information

• Increased decision-making flexibility at the local levels (where the work is being done)

For example, Eastman Kodak Company's new client/server ICBIS has resulted in a cooperative decision-making synergism, improving morale and strengthening communications while achieving large cost savings. The above Blockbuster Video case exemplifies the trend in downsizing and the distribution of computer resources to end users.

For many applications, the mainframe is still the only workable technology platform. The question is not whether a mainframe or LAN-based architecture is applicable. Rather, it is the dividing line between which applications should be run on a mainframe versus a smaller computer. This dividing line involves the following considerations:

• The size of the application. Some applications require gigabytes of online storage while pulling together data from numerous locations. LANs are not powerful enough to support many large-scale applications.

• The kind of application planned for the system. Some applications use millions of records with complex reporting modules. PCs may not possess fast enough processing speeds to handle such large databases.

• The number of end users. When the number of users enters the thousands, then a mainframe system may be necessary.

Decentralization requires interoperable architectures based on global enterprisewide systems supporting local end user decision making. Such an ICBIS design mirrors the organizational design. A key design tenet is assigning the right applications to the appropriate level and location of computer hardware. For example, mainframes process transactions that have already been edited, validated, and formatted by microcomputers, thereby updating the corporate database. LAN workstations provide a more friendly user interface for data input and queries, as demonstrated in the Simco case.

|

INSIGHTS & APPLICATIONS Interoperability at Simco Manufacturing Simco, a large steel fabricator, has grown, as many multinationals have, by acquiring smaller companies and setting them up as profit centers. Each RC had its own information system, leading to hardware, software, and data redundancies, as well as incompatible and sometimes conflicting information. James Kirby, Simco's CIO, designed an interoperable ICBIS with a centralized |

corporate database with online, real-time (OLRT) end-user access. After about six months of operation, Simco's RC managers favorably evaluated it pointing out that it allowed them access to different kinds of applications and information regardless of their location.The RC managers wanted and got an information system that allowed them to be able to run an application on whatever machine they happened to be at. This linkage provided interconnectivity of all nodes on the network and portability of applications to any node. With the previous system, Simco's LANs focused on isolated divisional needs rather than strategic interoperability with other segments of the company. |

HIERARCHICAL SEGMENTATION FOR PROFIT PERFORMANCE EVALUATION

LEARNING OBJECTIVE 2

Relate responsibility centers and responsibility accounting system design to profit performance evaluation.

Regardless of how RCs are created, the responsibility accounting system must measure the RC manager's success in achieving his or her master budget goals. Not all managers will have responsibility for the same financial factors, though. There are three financial factors:

• Cost

• Profit

• Investment

Some managers will control only costs. Others will control both cost and revenue to produce a profit. A few will be in charge of all three financial factors. A manager of an activity, such as transportation, will normally have responsibility only for certain costs. A product line manager may be assigned responsibility for that line's costs and revenues. A manager of a geographic division usually will be assigned responsibility for cost, revenue, and investment.

The Cost Center

A cost center is any RC where the manager can exert influence over cost but has little, if any, authority to influence revenues or investments in fixed assets. A production department and a maintenance department are good examples of a cost center. A cost center can produce a product or render a service.

Management accountants traditionally have used standard costs and cost variances to evaluate the performance of cost centers. An example of a detailed cost variance report for July's activities in producing Tigerade at Nulife Sports Drink, Inc., was presented in Exhibit 8-12. This case will also be used to develop the responsibility accounting reports for the product line (profit center) manager.

In addition to traditional cost variance reports, the responsibility accounting system should supply cost center managers with nonfinancial information needed for continuous improvement. Traditionally, many accountants and managers believed that the cost center manager was responsible only for monetary inputs (i.e., costs) and that the management accounting system only needed to relate these inputs to outputs. In today's competitive world, this approach is insufficient. An array of performance measurements are available to the management accountant to measure costs and report on how well these costs are being employed (i.e., performance measurements related to activities). A review of Part III, and especially Chapter 11, may be helpful at this point.

In general, the decision to use standard costs and cost variances is made considering the needs of both responsibility accounting and product costing. Traditional responsibility accounting systems using standard costs and flexible budgets have relied on the measurement and analysis of variances as the primary mechanism for performance evaluation.

This sole reliance on cost variance analysis for performance evaluation, especially the emphasis on labor-based measurements, has been the object of growing criticism from both academics and practitioners, however. By measuring and rewarding direct labor efficiency, other important criteria, such as competitive priorities of customer service, quality, lead time reduction, and on-time delivery are often minimized or ignored. Workers attempt to “play the system” by:

• Processing production orders with easily achievable standards ahead of those orders needed to meet delivery schedules

• Overloading the most efficient machines in spite of the availability of less efficient machines that would permit delivery schedules to be met

• Producing excess quantities to spread setup time and absorb fixed overhead

• Overlooking quality problems in order to achieve favorable efficiency variances

As responsibility accounting systems evolve, a variety of financial and nonfinancial performance measurements will be used, as presented in previous chapters. Moreover, standards or targets will be established for groups of interrelated RCs, where quality, lead time, cost, and customer objectives require that those centers behave as a team. Performance credit will be given to all RCs within the group when products are completed through the last RC.

The Profit Center

A profit center is any RC where the manager has the authority and responsibility to make decisions that will affect the costs and revenues of that center. The profit center manager, however, has little, if any, decision-making power concerning investments in fixed assets.

Clearly, the profit center manager needs information regarding costs and revenues. Proper performance evaluation compares the master budget and flexible budget against actual costs and revenues, reporting profit variances. Segmented income statements are output from the management accounting LAN for this purpose. Using the contribution margin format, “mini income statements” (segmented income statements) can be created for each RC. These mini income statements and their profit variance reports will be illustrated in the next major section of this chapter.

The Investment Center

An investment center is any RC where the manager has the authority and responsibility to make decisions that will affect the costs, revenues, and investments of that center. Thus, there is an expected return on investment on the assets deployed in the center. The investment center approach is usually applied to autonomous business units (i.e., divisions) and is rarely used in measuring the performance of internal service activities, such as logistics.

Profit analysis provides an appraisal of costs and revenues only. In an investment center, a third dimension should be evaluated: the amount of capital employed. How effective are the assets being used to generate revenue? Does the return on sales justify the investment? If not, what steps can be taken to correct the unfavorable performance?

To help investment center managers answer these questions and gauge their progress toward meeting their financial goals, management accountants use several financial performance measurements. Two of the most popular measurements are:

• Return on investment (ROI)

• Residual income (RI)

These will also be illustrated later in the chapter.

Levels of Reporting in Responsibility Accounting

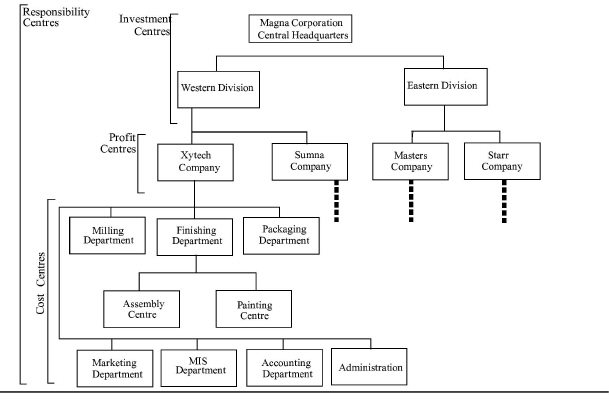

In decentralized organizations, the structure of the RCs may be similar to that of Magna Corporation shown in Exhibit 20-5

|

|

|

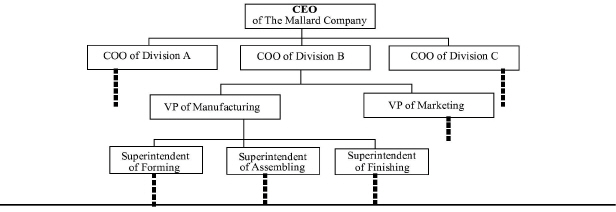

. At the highest level are the investment centers. At the company level are the profit centers. The lowest levels are the cost centers. Another objective of responsibility accounting is to tailor performance reports to their appropriate levels. Part of Mallard Company's organization chart is illustrated in Exhibit 20-6

|

Exhibit 20 -6 Responsibility Centres of Mallard Company |

|

. Only the bold-bordered blocks in the example will be used for illustrative purposes. Exhibit 20-7 illustrates the overhead reports for each RC and the relationship of each report to the next higher echelon of responsibility. Starting with report A at the bottom of Exhibit 20-7

|

D |

Summary of Mallard Company |

|

||

|

|

Overhead ($ 000) |

|

|

|

|

Reporting to CEO |

|

|

|

|

|

Company |

First Quarter |

|

Under <over> budget |

|

|

CEO |

$ 70 |

|

<$ 5> |

|

|

Division A |

460 |

|

30 |

|

|

Division B |

888 |

|

< 8> |

|

|

Division C |

200 |

|

< 22< |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

C |

Division B Overhead ($ 000) |

|

||

|

Division |

First Quarter |

|

Under <over> budget |

|

|

Division B |

$ 40 |

|

$ 5 |

|

|

Manufacturing |

700 |

|

< 33> |

|

|

Marketing |

148 |

|

20 |

|

|

Total |

$ 888 |

|

<$ 8> |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

B |

Manufacturing Overhead ($ 000) |

|

|

|

|

Department |

First Quarter |

|

Under <over> budget |

|

|

VP Manufacturing |

$ 50 |

|

<$ 2> |

|

|

Forming |

200 |

|

< 15> |

|

|

Assembling |

300 |

|

< 6> |

|

|

Finishing |

150 |

|

< 10> |

|

|

Total |

$ 700 |

|

<$ 33> |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

A |

Assembling Overhead ($ 000) |

|

|

|

|

Department |

First Quarter |

|

Under <over> budget |

|

|

Superintendent |

$ 5 |

|

$ 1 |

|

|

Makeup |

150 |

|

8 |

|

|

Welders |

145 |

|

< 15> |

|

|

Total |

$ 300 |

|

<$ 6> |

|

, the Assembling Department superintendent receives a detailed report that discloses the costs of the overhead items within his RC and the amount under or over the budget. Report B provides the vice president of manufacturing with performance figures for her RC, including the Forming, Assembling, and Finishing Departments within manufacturing. Report C provides the chief operating officer (COO) of Division B with performance figures for this division and summary figures for the manufacturing and marketing departments within Division B. Report D provides the CEO at company headquarters with summary figures for the three divisions that comprise the Mallard Company. Variances from budget can be traced downward through the organization as needed to show where management can control costs.

The Importance of Controllability in Responsibility Accounting

No matter what RC level is being evaluated, responsibility accounting is effective only when the RC manager being evaluated has internalized a sense of ownership, autonomy, and controllability. In order to ensure this, activities and financial factors deemed to be uncontrollable for a particular manager should be excluded when evaluating this person's performance. However, it is important to recognize that costs that are not controllable at a certain level are controllable elsewhere in the enterprise. For example, while the head of a department may have influence over the amount of space her area consumes, it is unlikely that she will have control over her own salary and benefits. In a responsibility accounting system, attention is directed toward managers and how much money they are spending to perform their activities. Successful operation of a responsibility accounting system therefore rests on two assumptions:

• Spending is subject to control.

• Responsibility for spending can be directly traced to a specific manager.

In practice, these assumptions contain some degree of subjectivity. As part of the strategic planning and master budgeting process, there must be consensus and agreement about who is responsible for budgeting and controlling each of the enterprise's activities. Explicit recognition of the responsibility assumptions is a prerequisite for a high-quality responsibility accounting system.

Indeed, the ability to control spending is not an absolute, but rather a matter of degree driven by:

• Level of authority

• Time

This does not mean that some spending is clearly controllable and other spending is definitely uncontrollable, but that all spending is controllable at some level of authority at some point in time. The manager of a production department may not control the expenditures for machines or the insurance for the machines in her department, but her manufacturing superintendent may. In summary, if a manager's decision can substantially influence the amount of spending, then the spending is assumed to be controllable by that manager.

Some companies report all profit center costs within segmented income statements and profit variance reports, even though some of the costs are not directly controllable by the managers. This approach is a violation of effective responsibility accounting, and creates ethical concerns in the areas of competency, integrity, and objectivity.

The rationale behind reporting uncontrollable costs is that it makes managers aware of the total costs of their activities. For example, even though an enterprise may be highly decentralized, some support services may be centralized at corporate headquarters. Often, ICBIS and accounting services, human resources departments, and some advertising activities are performed for the divisions. By allocating the costs of these corporate services to the divisions, using service department allocation techniques (Chapter 9) and activity-based costing techniques (Chapter 10), the divisional managers will be more aware of the costs and, consequently, so upper management believes, will not use these services wastefully or abuse them.

The modern management accountant must be very careful in allocating common corporate costs to the divisions. Not only do divisional managers seldom have control over the costs of these services, but if actual costs are allocated to the divisions, the corporate service center managers will have little incentive to control these costs. As Chapter 9 illustrated, traditional actual cost allocation systems, designed primarily for financial accounting purposes, can destroy the legitimacy of the responsibility accounting system.

Divisional managers may only have control over how much of a service they use. Consistent with the techniques described in Chapter 9, then, service department costs should be allocated using a budgeted rate for the variable costs and budgeted lump-sum allocations for the fixed costs. This will allow proper variance reporting in accordance with the controllability axiom. If a policy decision is made to include noncontrollable costs, such costs should be categorized separately in responsibility reports to emphasize that they are not considered controllable at that level.

Is There One Prescribed Way to Create Responsibility Centers?

Organization structures are too varied to permit generalization, as is readily apparent from the preceding description of the different ways to create RCs. Enterprises differ so widely in their goals, operations, philosophies, and personnel that no single form of organization structure and RCs will work for all of them. All RCs, however, require the following:

• Clear-cut lines of responsibility must be drawn.

• Responsibility must be coupled with commensurate authority.

Fuzzy lines of responsibility will bring only bickering and buck-passing. But giving RC managers responsibility for something they have no authority to control is even worse. Thus, to make the RC idea work, managers must be given clear responsibilities and sufficient authority to meet those responsibilities.

SEGMENTED INCOME STATEMENTS AND PROFIT CENTER PERFORMANCE EVALUATION

LEARNING OBJECTIVE 3

Segment the profit center's income statement for segment and manager performance evaluation.

In evaluating a profit center's financial performance, the management accounting system has two basic goals:

• To report on the profitability of the segment

• To report on the performance of the segment manager

First, this section will present two formats for the segmented income statement. Then, reporting for each of the two goals will be examined. Finally, the usefulness of segmented income statements in the decision to continue or drop a product line will be addressed.

Functional Form and Contribution Margin-Based Income Statements

For financial reporting, the income statement organizes costs by their functions (product costs versus operating expenses). This format also employs absorption costing in that fixed overhead is absorbed into the product cost. When segmenting an income statement, using the absorption costing principle, indirect costs (common fixed costs across all profit centers) are allocated to (absorbed by) the profit centers, as presented in the Nulife case.

As Exhibit 20-8 shows, Nulife has been allocated $30,000 in common corporate costs.1 Of this amount, $18,000 was allocated to Tigerade and $12,000 was allocated to Lions Crunch. The controller explained to Karen that these allocations are for corporate services provided to the profit centers, such as centralized accounting and human resources department costs.

|

INSIGHTS & APPLICATIONS Nulife Sport Drink, Inc. This case is a continuation of the case used in Chapter 8 to illustrate cost variance reporting. Nulife has segmented itself by product line. Tigerade sports drink is one of Nulife's profit centers. The manager of this segment, J. B. Fuller, has just introduced a new related product line, Lions Crunch health bars. Both products are considered to be within this profit center.In attempting to establish Lions Crunch, Nulife has |

marketed it in two regions, the East Coast and the West Coast. J. B. Fuller has just received his July income statement, segmented by product line. This is presented in Exhibit 20-8. Obviously, he is concerned about the poor reported performance of Lions Crunch, and he has asked the new management accountant, Karen Rosenau, to analyze it and report back to him. After consulting with the corporate controller, Karen believes the company is using good absorption costing techniques for financial reporting purposes. However, she also believes that reformatting the income statement based on a contribution margin approach, as illustrated in chapters 18 and 19, can provide more useful information for evaluating the real profitability of Lions Crunch. |

Upon further investigation, Karen discovered that Nulife uses a very common allocation method. These actual costs are allocated based on the relative sales revenues of each product. Tigerade, generating $360,000 of Nulife's $600,000 total revenues (which is 60 percent), was allocated 60 percent of the common corporate costs. Lions Crunch generated 40 percent of Nulife's revenues ($240,000) and was allocated 40 percent of the $30,000. This allocation method has been justified by an “ability to bear” philosophy. The more revenues a product creates, the greater its ability to absorb (“bear”) the common fixed costs.

Karen is suspicious of this technique, though, when it is used in evaluating product profitability and profit center manager performance. As she explained to J. B., if sales revenues of one product go down, then the allocation of common fixed costs will also go down, making the product look more profitable. Allocations to the other products will then increase, making them look worse, even though there may not have been any real change in their profitability.

To illustrate this to J. B., Karen prepared the analysis following Exhibit 20-8. Assume that Tigerade revenues drop $100,000 to $260,000.

|

|

Tigerade |

Lions Crunch |

Nulife Totals |

|

Revenues |

$360,000 |

$240,000 |

$600,000 |

|

Less cost of goods sold: Variable manufacturing costs |

225,250 |

60,000 |

285,250 |

|

Fixed manufacturing costs |

12,100 |

25,000 |

37,100 |

|

Total production costs |

<237,350> |

<85,000> |

<322,350> |

|

Gross profit |

$122,650 |

$155,000 |

$277,650 |

|

Less selling and administrative expenses: Variable selling costs |

44,750 |

80,000 |

124,750 |

|

Fixed selling and administrative costs |

47,900 |

65,000 |

112,900 |

|

Allocated corporate costs |

18,000 |

12,000 |

30,000 |

|

Total selling and administrative costs |

<110,650> |

<157,000> |

<267,650> |

|

Net income |

$ 12,000 |

<$ 2,000> |

$ 10,000 |

|

|

Tigerade |

Lions Crunch |

Nulife totals |

|

New sales revenues |

$260,000 |

$240,000 |

$500,000 |

|

New relative sales revenue ratios |

52% |

48% |

100% |

|

New allocation of common corporate costs |

$15,600 |

$14,400 |

$30,000 |

|

Change in allocation of common corporate costs |

<$2,400> |

+$2,400 |

-0- |

Because Tigerade revenues decreased, the allocated common costs went down for Tigerade. In effect, this makes Tigerade appear more profitable than it is. Tigerade's variable cost ratio is 75 percent (($225,250 + $44,750) - $360,000) and its CM ratio is 25 percent. If Tigerade revenues go down by $100,000, then its contribution margin and net income drop $25,000 (CVP rules 4 and 1, respectively, Exhibit 18-3). The decrease in Tigerade profits of $25,000 is partially masked by the $2,400 reduction in allocated common corporate costs.

Meanwhile, there was no real change in the sales, costs, or profits of Lions Crunch. But, because Tigerade revenues went down, Lions Crunch is now allocated another $2,400 in common corporate costs. This makes Lions Crunch's profit performance look worse, when there should be no difference.

With respect to J. B.'s performance evaluation, she argued that the allocated common corporate “overhead” should not be included in evaluating a manager's performance. J. B. Fuller has no control over the costs of these corporate services, especially the actual costs. They should also not be considered in evaluating the segment's real profit contribution to covering overall corporate costs and generating profits.

J. B. Fuller was perplexed. He has no control over the costs of the common corporate services, nor is he allowed to outsource these services if he can obtain them cheaper from another supplier, or perform them within his profit center if he can do it cheaper than corporate headquarters. Karen agreed. Both in measuring the real profitability of the products and in evaluating J. B. Fuller's performance, these common fixed costs should not be included. To determine the real profitability of the products, Karen created a worksheet in a spreadsheet program to segment the income statement by product line, using a contribution margin approach that separates the allocated common fixed corporate costs from the direct costs of each product line. This format is displayed in Exhibit 20-9.

The only difference in the product net incomes between the two income statement formats is that allocated common fixed costs are included under the functional form, absorption costing-based income statement in Exhibit 20-8, whereas under the contribution margin-based approach, the common fixed costs are reported separately just in the totals column. The functional form, absorption costing-based income statement allocates all costs to all product lines. The contribution margin-based income statement format organizes costs by behavior and separates the common fixed costs from the direct fixed costs of the segments.

Evaluating Profit Center Profitability

Karen believes that by separating the common fixed costs from the direct fixed costs, a better measure of the true profitability of the product lines results.

|

|

Tigeradea |

Lions Crunch |

Nulife Totals |

|||||

|

|

Per unitb |

Percent |

Totals |

Per unit |

Percent |

Totals |

Percent |

Totals |

|

Revenues |

$40 |

100% |

$360,000 |

$24 |

100% |

$240,000 |

100% |

$600,000 |

|

Less variable costs: Variable manufacturing costs |

25 |

63% |

225,250 |

6 |

25% |

60,000 |

47% |

285,250 |

|

Variable selling costs |

5 |

12% |

44,750 |

8 |

33% |

80,000 |

21% |

124,750 |

|

Total variable costs |

<30> |

<75%> |

<270,000> |

<14> |

<58%> |

<140,000> |

<68%> |

<410,000> |

|

Contribution margin |

$10 |

25% |

$ 90,000 |

$10 |

42% |

$100,000 |

32% |

$190,000 |

|

Less direct fixed costs: Fixed manufacturing costs |

|

12,100 |

|

|

25,000 |

|

37,100 |

|

|

Fixed selling and administrative costs |

|

|

47,900 |

|

|

65,000 |

|

112,900 |

|

Total fixed costs |

|

|

<60,000> |

|

|

<90,000> |

|

<150,000> |

|

Segment margin |

|

|

$ 30,000 |

|

|

$ 10,000 |

|

$ 40,000 |

|

Less common fixed costs |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

<30,000> |

|

Net income |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

$ 10,000 |

|

aSales volume for Tigerade = 9,000 cases; sales volume for Lions Crunch = 10,000 cases. bThe per unit and percent columns are calculated by working backwards from the totals column. For example, the $225,250 total variable manufacturing costs for Tigerade (from Exhibit 8-12) divided by 9,000 cases = $25.0278 per case. Dividing $225,250 by Tigerade revenues of $360,000 = 62.5694% for the percent column. The per unit and percent columns are formatted to the nearest whole dollar and percentage for clarity in presentation. |

THE USEFULNESS OF SEGMENT MARGINS. The “direct” profit generated by each product line is measured in its segment margin. In Exhibit 20-9, J. B. Fuller sees that each product creates positive profits for use in covering the common fixed costs of Nulife and in generating overall corporate profits. In other words, Tigerade contributed $30,000 in direct profits and Lions Crunch contributed another $10,000.

J. B. found this format more useful because it reports each product's contribution margin for use in short-run decisions (illustrated in Chapters 18 and 19), as well as each product's segment margin for use in evaluating the profitability of those segments.

SUBSEGMENTING PRODUCT LINES INTO GEOGRAPHIC TERRITORIES. J. B. Fuller is also interested in the profitability of the two sales territories where Lions Crunch has been test marketed. So, he asked Karen to use her spreadsheet program to create a Lions Crunch income statement segmented by East Coast and West Coast. Exhibit 20-10 presents her report.

Karen explained to J. B. how she prepared her report. First, the Lions Crunch income statement in Exhibit 20-9 is the same as in the Lions Crunch Totals column of Exhibit 20-10. Lions Crunch direct fixed selling and administrative costs (Exhibit 20-9) were $65,000 in July. Of this amount, $50,000 represented selling expenses directly traceable to each sales territory ($10,000 on the East Coast and $40,000 on the West Coast).

The remaining $15,000 (of the $65,000 total) represented common administrative costs of Lions Crunch. Both regions are serviced by a single manufacturing plant, so its $25,000 in FOH is also common to the territories. Therefore, neither of these amounts is included in the regional segment margins. Instead, these costs are separately reported only in the Totals column for Lions Crunch (Exhibit 20-10). To summarize, of the $90,000 in direct fixed costs of Lions Crunch, $50,000 is directly traceable to each region and $40,000 is common to them.

|

|

East Coasta |

West Coast |

Lions Crunch |

|||||

|

|

Per unitb |

% |

Totals |

Per unit |

% |

Totals |

% |

Totals |

|

Revenues |

$24 |

100% |

$96,000 |

$24 |

100% |

$144,000 |

100% |

$240,000 |

|

Less variable costs: Variable manufacturing costs |

6 |

25% |

24,000 |

6 |

25% |

36,000 |

25% |

60,000 |

|

Variable selling costs |

5 |

21% |

20,000 |

10 |

42% |

60,000 |

33% |

80,000 |

|

Total variable costs |

<11> |

<46%> |

<44,000> |

<16> |

<67%> |

<96,000> |

<58%> |

<140,000> |

|

Contribution margin |

$13 |

54% |

$52,000 |

$ 8 |

33% |

$ 48,000 |

42% |

$100,000 |

|

Less direct fixed selling costs |

|

|

<10,000> |

|

|

<40,000> |

|

<50,000> |

|

Segment margin |

|

|

$42,000 |

|

|

$ 8,000 |

|

$ 50,000 |

|

Less common fixed costs: Fixed manufacturing costs |

|

|

|

|

|

25,000 |

||

|

Fixed administrative costs |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

15,000 |

|

Total fixed costs |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

<40,000> |

|

Net income |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

$ 10,000 |

|

aSales volume for East Coast = 4,000 cases; sales volume for West Coast = 6,000 cases. bSee note b in Exhibit 20-9 concerning calculations of per unit and percentage amounts. |

J. B. Fuller now has a better picture for evaluating the profitability of each region. While both contributed positively, the East Coast significantly outperformed the West Coast. This was expected, J. B. explained to Karen. Attempting to penetrate the very competitive West Coast was expensive. Variable selling expenses (coupons, higher commissions to retail jobbers) were twice as high as on the East Coast. This caused a lower CMU and CM ratio for the West Coast. Furthermore, fixed advertising costs were four times greater than on the East Coast. One bit of good news, though, was that West Coast sales actually were higher than the East Coast.

Evaluating Profit Center Manager Performance

J. B. Fuller then returned to his analysis of Tigerade and Lions Crunch (Exhibit 20-9). “Well, I guess I should give those two accounting interns you suggested I hire to manage each product line a bonus. It looks like the Tigerade intern should get three times the bonus of the Lions Crunch intern, though.”

Karen interrupted with a warning, “The segment margins may not be the best performance measure for evaluating a manager. Some of the direct fixed costs of a segment may not really be controllable by the segment manager. For example, if a division provides its segments with administrative services, including accounting, ICBIS, and/or advertising, then these costs should be separated from the direct fixed costs that the segment managers can control.”

J. B. responded, “O.K., they had control over their production, distribution, and sales. So these costs should be controllable direct costs of the product lines2. But wait a minute, the interns have no control over their own salaries. I control that. So keep the salaries within the calculations of the segment margins, but separate them from the controllable direct fixed costs.”

THE USEFULNESS OF CONTROLLABLE SEGMENT MARGINS. Karen modified her spreadsheet program by separating the direct fixed costs of each product line ($60,000 and $90,000 in Exhibit 20-9) into those that were controllable by the managers and those that were not. Her new report is shown in Exhibit 20-11. The fixed selling expenses within each product were separated from the salaries of the accounting interns (that were journalized and posted to individual product line administrative expense accounts within the accounting system). Karen created a new subtotal, controllable segment margin. This can be used to evaluate the profit created from the activities under the control of the managers. Controllable segment margin includes only those activities for which the manager has decision-making responsibilities.

J. B. Fuller was impressed. “Based on this report, I think I should only give twice the bonus to the Tigerade intern. His decisions generated $50,000 toward covering common fixed costs and creating profits, while the Lions Crunch intern generated only $25,000 in controllable segment margin.”

Again Karen interrupted with a warning. “The segments may not be directly comparable. We have to guard against falling into the 'deadly parallel evaluation strategy' without first comparing their performance against their budgets. For example, using the controllable segment margins that actually resulted does not take into consideration differences between the two segments that are reflected in their budgets.

“We should not just automatically compare the actual results of each segment, nor should we compare only the actual performance of a segment against its previous year. Although this has been a common practice at Nulife, there is no guarantee that this year is comparable to last year. A number of strategic and environmental factors could make the actual results of one year completely different from the actual results of another year.

|

|

Tigeradea |

Lions Crunch |

Nulife Totals |

|||||

|

|

Per unitb |

% |

Totals |

Per unit |

% |

Totals |

% |

Totals |

|

Revenues |

$40 |

100% |

$360,000 |

$24 |

100% |

$240,000 |

100% |

$600,000 |

|

Less variable costs: Variable manufacturing costs |

25 |

63% |

225,250 |

6 |

25% |

60,000 |

47% |

285,250 |

|

Variable selling costs |

5 |

12% |

44,750 |

8 |

33% |

80,000 |

21% |

124,750 |

|

Total variable costs |

<30> |

<75%> |

<270,000> |

<14> |

<58%> |

<140,000> |

<68%> |

<410,000> |

|

Contribution margin |

$10 |

25% |

$ 90,000 |

$10 |

42% |

$100,000 |

32% |

$190,000 |

|

Less controllable direct fixed costs: Fixed manufacturing costs |

|

|

12,100 |

|

|

25,000 |

|

37,100 |

|

Fixed selling costs |

|

|

27,900 |

|

|

50,000 |

|

77,900 |

|

Total controllable direct fixed costs |

|

|

<40,000> |

|

|

<75,000> |

|

< 115,000> |

|

Controllable segment margin |

|

|

$ 50,000 |

|

|

$ 25,000 |

|

$ 75,000 |

|

Less uncontrollable direct fixed costs: Fixed administrative costs |

|

|

<20,000> |

|

|

<15,000> |

|

<35,000> |

|

Segment margin |

|

|

$ 30,000 |

|

|

$ 10,000 |

|

$40,000 |

|

Less common fixed costs |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

<30,000> |

|

Net income |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

$ 10,000 |

|

aSales volume for Tigerade = 9,000 cases; sales volume for Lions Crunch = 10,000 cases. bSee note b in Exhibit 20-9 concerning calculations of per unit and percentage amounts. |

For example, remember the manager of our gourmet health food product line at last year's bonus meeting? He argued that this line's profitability had increased substantially over the previous year and that he should receive a substantial bonus. However, the corporate controller pointed out that in the previous year, the manager's actual profits were below that year's master budget. Further, the difference between his actual and budgeted profits last year was even worse than in the previous year!

|

|

Master Budget (Volume = 10,000) |

Sales Volume Variance |

Flexible Budget (Volume = 9,000) |

Actual Profit Totals |

Flexible Budget Variances |

|||

|

|

Per unit |

Totals |

|

Per unit |

Totals |

|

|

|

|

|

|

(a) |

(b - a) |

|

(b) |

(c) |

(d)* |

|

|

Revenues |

$35 |

$350,000 |

|

$35 |

$315,000 |

$360,000 |

$45,000 |

F |

|

Less variable costs: Variable manufacturing costs |

26 |

260,000 |

|

26 |

234,000 |

225,250 |

8,750 |

F |

|

Variable selling costs |

5 |

50,000 |

|

5 |

45,000 |

44,750 |

250 |

F |

|

Total variable costs |

<31> |

<310,000> |

|

<31> |

<279,000> |

<270,000> |

9,000 |

F |

|

Contribution margin |

$ 4 |

$ 40,000 |

<$4,000> U |

$ 4 |

$36,000 |

$90,000 |

$54,000 |

F |

|

Less controllable direct fixed costs: Fixed manufacturing costs |

|

12,000 |

|

|

12,000 |

12,100 |

<100> U |

|

|

Fixed selling costs |

|

28,000 |

|

|

28,000 |

27,900 |

100 |

F |

|

Total controllable direct fixed costs |

|

<40,000> |

|

|

<40,000> |

<40,000> |

-0- |

|

|

Controllable segment margin |

|

$ -0- |

<$4,000> U |

|

<$4,000> |

$ 50,000 |

$54,000 |

F |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

While year-to-year comparisons are important in measuring long-run continuous improvement, these comparisons should be between the annual budgets of the segment. Annual budget-to-budget comparisons are important for moving toward world-class status. Budget-to-actual comparisons for a particular time period (such as July or the year) are just as important, though, in measuring short-run operating performance.” Karen prepared a spreadsheet program to compare July's budgeted and actual performance for each product line manager. Only the Tigerade report is illustrated in Exhibit 20-12.

PROFIT VARIANCE ANALYSIS. Karen's report includes only those activities that are controllable by the segment manager. In other words, the income statement ends with controllable segment margin. She felt this was important

|

Exhibit 20 -13 Detailed Tigerade Profit Variance Report |

|||

|

|

Spending |

Usage |

Totals |

|

Sales variances: Sales volume variance |

|

|

<$ 4,000>% |

|

Sales price variance |

|

|

45,000 |

|

Total sales variances |

|

|

$41,000 |

|

Selling and administrative expenses variances: Variable costs |

$ 250 |

|

250 |

|

Fixed costs |

100 |

|

100 |

|

Total S & A variances |

$ 350 |

|

$ 350 |

|

Production costs variances: Direct materials |

<4,000> |

<$3,000> |

<7,000> |

|

Direct labor |

8,750 |

5,000 |

13,750 |

|

Variable overhead |

1,250 |

750 |

2,000 |

|

Fixed overhead |

<100> |

n/a |

< 100> |

|

Total production variances |

$5,900 |

$2,750 |

$ 8,650 |

|

Variance totals |

|

|

$50,000 |

|

|

|

|

|

Note: Favorable variances are positive amounts, unfavorable variances are negative amounts.

Tigerade monthly controllable segment margin = (CMU x Volume) - Controllable direct fixed costs

For the master budget sales quota of 10,000 cases of Tigerade:

Tigerade monthly controllable segment margin = ($4 per case x 10,000 cases) - $40,000= $0

For the actual sales volume of 9,000 cases, the flexible budget profit is:

Tigerade monthly controllable segment margin = ($4 per case x 9,000 cases) - $40,000 = <$4,000>

Because the sales volume variance explains the difference between planned and actual profits due to selling a different volume than budgeted, it is shown between the master budget and the flexible budget in Exhibit 20-12. It is also reported as the first sales variance in Exhibit 20-13.

The flexible budget variances (the last column in Exhibit 20-12) are the differences between the flexible budget amounts and the actual results. Actual sales revenues were $45,000 greater than budgeted for this volume (9,000 cases). This is due to the actual sales price being higher than the budgeted sales price. The difference between planned and actual profits due to a difference in budgeted and actual sales prices is captured in the sales price variance:

Sales price variance = Actual sales volume X (Actual sales price - Budgeted sales price)

= 9,000 cases X ($40 per case - $35 per case)

= $45,000 favorable

In interpreting this variance to J. B. Fuller, Karen explained that if sales price increases $5 per unit, then CMU will increase $5. For 9,000 cases, contribution margin and profits will then increase $45,000 over budget.

After explaining the sales variances, Karen moved to the selling and administrative expenses variances. She calculated spending variances by just subtracting the actual costs from the flexible budget costs. Although the variances were favorable in July, they were insignificant, representing only 0.5 percent of the flexible budget amounts [$350 - ($45,000 + $28,000)]. She then concluded with the production cost variances. These are summarized in the last section of Exhibit 20-13. Their detailed calculations, in total dollars, per unit, and as a percentage of standard, are presented in Exhibit 8-12.

J. B. Fuller had only one more question. “Why wasn't the FOH volume variance reported in either Exhibit 20-12 or 20-13?” This was a little hard for Karen to explain, so she began with the following calculations:

FOH volume variance = FOH standard cost X (Actual volume - Budgeted volume)

= $1.20 per case X (9,000 cases - 10,000 cases)

= <$1,200> unfavorable

Other fixed costs volume variance = Other fixed standard costs X (Actual volume - Budgeted volume)

= $2.80 per case X (9,000 cases - 10,000 cases)

= <$2,800> unfavorable

From Tigerade's standard cost card (Exhibit 8-11), the sales price needs to be marked up $1.20 (the FOH standard cost) above variable costs to provide sufficient contribution margin to pay for the total FOH. This assumes that 10,000 cases of Tigerade will be sold. Also assuming 10,000 cases of sales volume, the sales price will have to be marked up another $2.80 ($28,000 / 10,000 cases) to cover the other fixed selling and administrative costs. In total, Tigerade's sales price needs to be $4.00 higher than its variable cost. In other words, it has to generate a $4.00 CMU to cover fixed costs and target profit (which was budgeted at zero) if 10,000 cases are sold.

But 10,000 cases were not sold. The lost contribution margin from lower actual sales is captured in the sales volume variance. The $4.00 CMU used in the formula includes $1.20 for FOH and $2.80 for other fixed costs. Therefore, the FOH volume variance is already included in the sales volume variance. This is why Karen reported it as not applicable (n/a) in Exhibit 20-13.

J.B. now understood the need for profit variance analysis when evaluating managers' performance. Before he could decide on bonuses, he asked Karen to prepare a similar analysis for Lions Crunch.

LEARNING OBJECTIVE 4

Identify the relevant profit elements for the add-or-drop decision, and describe how' product life cycle analysis and the growth/share matrix are used.

The Add-or-Drop Decision

The add-or-drop decision deals with whether to add, drop, or continue a particular product, line of products, enterprise segment, or service. Both qualitative and quantitative factors must be considered when making such decisions. Ultimately, however, any decision to add or drop a product, product line, department, or territory is going to center on the impact the decision will have on overall enterprise profits.

CONSIDERING QUALITATIVE FACTORS. The decision to add or drop a product, product line, segment, or service is often complicated by various marketing considerations. Many enterprises believe they are obligated to carry a range of sizes, colors, styles, flavors, or related items. These marketing factors can outweigh persuasive quantitative data to the contrary.

Often certain products are sold at a loss (based on full costs) in order to attract customers. For example, a shoe store may sell socks at $1 a pair to attract customers to the store in the hope of selling shoes at regular price. In some enterprises, these “loss leaders” are considered an integral part of marketing strategy. These qualitative issues represent legitimate factors that management accountants must consider.

CONSIDERING QUANTITATIVE FACTORS. If the question involves dropping a product, service, or segment, then only the fixed costs that can be avoided by dropping the item are subtracted from that item's contribution margin. If the result is positive, then the item should be kept (or added) because this amount increases the profits of the enterprise. The Computerworld case on the next page demonstrates this analysis.

Direct fixed costs are directly traceable to each product line, but they may or may not be avoided if the product line is dropped. All or part of these costs may be sunk costs that will continue even if the product line is dropped. Indeed, this is the situation at Computerworld because a large portion of the direct fixed costs for office supplies is depreciation on display racks and cases. Moreover, managers of the office supplies product line will be kept on the payroll even if the product line is dropped, although some employees who specialize in office supplies will be discharged. In Computerworld's case, the $16,000 in direct fixed costs is composed of the following items (in thousands):

|

Cost Item |

Avoidable |

Unavoidable |

|

Depreciation of display racks and cases |

|

$ 7 |

|

Salaries of managers |

|

4 |

|

Salaries of discharged employees |

$5 |

|

|

Total direct fixed costs |

$ 5 |

$11 |

The common fixed costs of $18,000 cannot be avoided by dropping the office supplies product line, because they are composed of store rent and general management salaries that will continue even if office supplies are dropped. .

|

INSIGHTS & APPLICATIONS Computerworld's Product Line Cost Analysis Computerworld is a small retail chain that sells personal computers, peripherals such as printers, software packages, and office supplies. Management of Computerworld is concerned about the loss in the office supplies line as reported on the functional form, absorption costing-based income statement used for financial reporting. |

Common fixed costs of $18,000 were allocated to it, resulting in a reported loss of $4,000.' Several managers have recommended that to improve the company's overall net manage-income, office supplies must be dropped. The management accountant for Computerworld explained that the decision rests on what costs can be avoided to offset the loss in contribution margin if the office supplies product line is dropped. She went on to tell them that both direct fixed costs and common fixed costs must be considered. Data (in thousands of dollars) on these four product lines for the past month are as follows: |

The company originally expected that some of the common fixed administrative costs could be avoided, such as reducing the accounting staff, but upon further investigation, this does not appear likely. Therefore, the common fixed costs are unavoidable regardless of the decision with respect to office supplies.

If Computerworld drops the office supplies product line, the company's overall net income will decrease by $25,000 each month. Computerworld will lose $30,000 in contribution margin and only avoid (save) $5,000 in direct fixed costs

|

|

PCs |

Peripherals |

Software packages |

Office supplies |

Totals |

|

Sales |

$800 |

$200 |

$400 |

$300 |

$1,700 |

|

Variable costs |

<500> |

<100> |

<250> |

<270> |

<1,120> |

|

Contribution margin |

300 |

100 |

150 |

30 |

580 |

|

Direct fixed costs |

<150> |

<40> |

<70> |

<16> |

<276> |

|

Segment margin |

$150 |

$ 60 |

$ 80 |

$ 14 |

$ 304 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

SUPPLEMENTARY METHODS USED IN THE ADD-OR-DROP DECISION. Two supplementary methods are available that can help in making the add-or-drop decision:

• Product life cycle analysis

• Growth/share matrix

Using Product Life Cycle Analysis

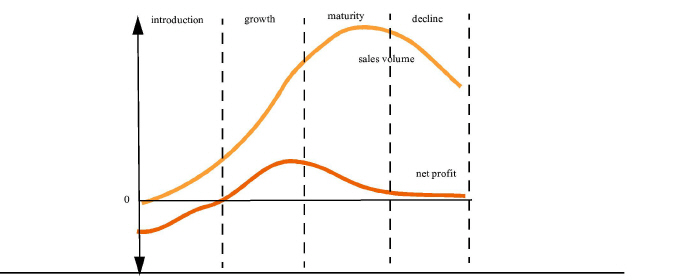

Product life cycle analysis is a useful aid to managers who must determine how to allocate scarce resources to products or product lines in a manner that will maximize enterprise profitability. 3 A graph of sales volume and net profit at various stages of the product life cycle is presented in Exhibit 20-14.

|

Managers can use the product life cycle graph to monitor product profitability and to drop products when they become unprofitable. In the maturity and decline stages, it is important to determine if other products will contribute more per dollar of cost. At some point during the decline stage, management may decide to hasten the product's decline so that cash can be generated to support products that will sustain the enterprise's profitability in the long run4. A good example is Intel's efforts in 2005 to supplant its less profitable 386 microprocessor with the 486 chip, although the 386 was nowhere near the end of its life cycle. In 2008, Intel introduced the Pentium, to replace the 486 microprocessor. There are many examples of this in recent business history.

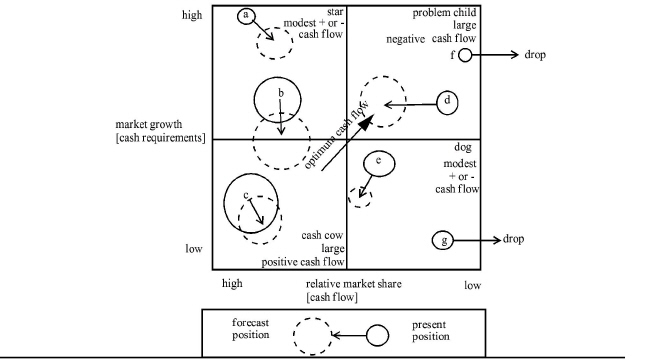

Using the Growth/Share Matrix

The growth/share matrix is based on the following assumptions

• Cash flow is a measure of business success.

• Cash use is a function of market growth.

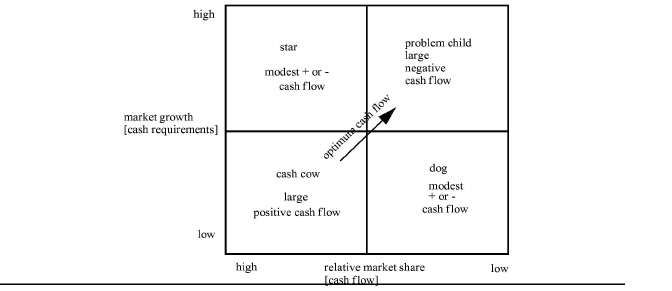

• Cash generation is a function of the product's market share. The result is a growth/share matrix like the one illustrated in Exhibit 20-15. Each quadrant describes a different type of product with fundamentally different cash flow positions and specific characteristics. Each type of product requires a specific management strategy:

• Cash cows. Because of their high market share, these products generate more cash than is required by the low-growth market in which they operate. These products provide the main source of cash and earnings to the enterprise and can be used to fund other developing products, such as in the Lotus example on the next page. The arrow in Exhibit 20-15 demonstrates how proceeds from cash cows are used to support problem children.

• Stars. These products generate a large gross cash flow, but most of the cash is used to support their high growth rate. As growth slows, stars become cash cows. These products represent the future of the company.

• Problem children. These products generate little cash because of their low market share. At the same time, they require large amounts of cash to support their high growth rate. The company must decide whether to try to achieve a high market share for these products by turning them into stars and ultimately cash cows or to drop them altogether.

• Dogs. These products neither generate nor require much cash. Because of their low market share and low growth, dogs offer little opportunity for future profits. Generally, the most effective decision is to drop these products.

Preparing product profitability reports that show cash flows is one method that is used to validate the positioning of products on the growth/share matrix. The management accountant plays a significant role in this process.:

|

The growth/share matrix can also be expanded to show both the present and future positions of each product as determined by product life cycle analysis and the marketing strategy of the enterprise. For example, Exhibit 20-16 highlights the following strategies for products A through G:

• Aggressively support newly introduced product A to ensure dominance

• Continue present strategies for products B and C to ensure maintenance of market share

• Gain share of market for product D by investing in acquisitions

• Narrow and modify the range of models of product E to focus on one segment

• Drop products F and G5

Segmented Income Statements and Performance Evaluation in Summary

In summary, a high-quality profit management system will include the separation of direct from common fixed costs in segmenting profit center income statements. Subtracting the direct fixed costs from a segment's contribution margin creates a new subtotal called “segment margin.” The segment margin is a useful measure of segment profitability.

|

However, the segment margin cannot be used in deciding whether to continue or discontinue the segment. Consideration has to be given to the avoidable costs involved in this decision. Not all direct fixed costs are avoidable. Some of the fixed assets, and the depreciation expense they create, may continue to be used. If so, then these future costs are not different between the alternatives to continue or discontinue the segment. If they are not differential costs, then they are not relevant to this decision6. Analogously, if some of the people currently employed within this segment will be reassigned (instead of terminated), then their labor costs are not relevant to this decision.

|

INSIGHTS & APPLICATIONS Taking Care of the Cash Cow By the mid-1090s Lotus Development Corporation had pumped over $100 million into a groupware product called Notes, which is designed to improve communication among users. by 1995 Lotus had not made much of a return on its Notes investment. Key employees have left, unconvinced that the company's future lies with Notes rather than its cash cow, the Lotus 1-2-3 spreadsheet. At that time Lotus 1-2-3 generated two-thirds of the company's revenue. |

Lotus was totally dependent on 1-2-3 profits to fund research and development for other products. But today, Lotus Notes® is hailed as a breakthrough product that allowed people to access, track, share, and organize information throughout the enterprise. It is now owned by IBM and is a premier bib business product. Lotus managers said the company shifted toward Notes realizing it couldn't maintain growth in a mature, competitive spreadsheet market. Now, of course Lotus 1 2 3 does not exist, however it is an iconic product that migrated through the different phases described in this chapter. |

Consideration should also be given to whether any common fixed costs will change if a segment is dropped. Sometimes corporate support services can be downsized if less services are now needed. These cost savings become relevant to this decision. Finally, in making the add-or-drop decision, supplemental analyses such as the product life cycle graph and the growth/share matrix may be helpful.

When evaluating the performance of a segment manager, the direct fixed costs within a segment need to be broken down into those that are controllable and those that are uncontrollable. The subtotal controllable segment margin that results from subtracting only the controllable direct fixed costs from the segment's contribution margin is useful for evaluating the performance of the profit center manager. However, proper performance evaluation requires the comparison of actual results against the master budget. Therefore, profit variances need to be calculated and reported to those responsible for them. Exhibit 20-17 summarizes the steps in preparing and using segmented income statements.

|

To prepare the segmented income statement: 1. Identify the allocation of common fixed costs and remove it from the segment. 2. Using only the direct fixed costs of a segment, calculate its segment margin. 3. Break down the direct fixed costs into controllable direct fixed costs versus uncontrollable direct fixed costs. 4. Using only the controllable direct fixed costs, calculate a new subtotal called the controllable segment margin. |

|

Using the segmented income statement in decision making: 1. Use the segment margin to measure segment profitability. 2. To evaluate the performance of the segment manager, use the controllable segment margin. This should be compared against the master budget, with profit variances reported. 3. When making a decision about adding or dropping segments: a. Adjust the segment margin by changing the direct fixed costs to the avoidable direct fixed costs. The result is the segment margin lost by dropping the segment. b. Prepare graphical analyses such as the growth/share matrix and the product life cycle graph. |

EVALUATING INVESTMENT CENTER PROFITABILITY

LEARNING OBJECTIVE 5

Calculate profit performance measures for investment center managers.

Investment center managers are also responsible for profit management. Thus, segmented income statements are the first step in evaluating the profitability of investment centers and their managers. At this level of an enterprise's management hierarchy, however, asset investment responsibilities should be included in the analysis. Two commonly used financial measures of asset profitability are:

• Return on investment (ROI)

• Residual income (RI)

Return on Investment

Return on investment (ROI) (also called return on assets) is comparable to an interest rate on a savings account. If one dollar is invested in a savings account for one year and earns six cents in interest, then this account's simple interest rate is 6 percent. The return earned on this one-dollar investment is 6 percent.

A very common technique in reporting profits is to calculate profits as a percentage of sales. Many profit center managers relate to sayings such as, “My profit margin last month was 15 percent.” In other words, each dollar of sales returned 15 cents in net income. Investment center managers, concerned with asset investments, relate to returns (profits) measured against assets instead of sales revenues. ROI is computed as follows:

ROI = (Investment center net income) / (Investment center assets)

For the one-dollar savings account's interest rate calculation:

ROI = $0.06 per year / $1.00 = 6%

While ROI is a useful measure of the rate of return on investments, it can provide even more meaningful information if it is decomposed into its two component ratios. Profit margin is income divided by sales revenues. It is a short-term measure of operating efficiency, evaluating how much profit is generated from a dollar of sales. Asset turnover ratio is revenues divided by assets. It is a longer-term measure of the effectiveness of asset usage. This ratio provides a measure of how effective a dollar investment is in creating sales revenues. When multiplied together, these two ratios yield ROI:

|

|

Profit margin |

|

Asset turnover |

|

|

Investment center net income |

x |

Investment center sales |

|

ROI = |

Investment center sales |

|

Investment center assets |

Notice that the investment center's total sales revenue is the denominator of the first ratio and the numerator of the second. Mathematically, the two ratios can be reduced to ROI. From a performance evaluation perspective, though, each component ratio provides important information. The profit margin focuses on the rate of earnings generated by each sales dollar. Asset turnover focuses on the use of assets and indicates the rate at which sales are being generated for each dollar invested.

This decomposition also focuses attention on how investment center managers can improve their ROI:

• By increasing sales

• By reducing costs

• By reducing assets

For example, Exhibit 20-18 reports the ROIs for the two Magna Corporation investment centers previously illustrated in Exhibit 20-5. Although the Eastern and Western Divisions have the same profit margins, the Eastern Division's asset turnover is larger than the Western Division's (1.25 times compared to 0.80 times). In interpreting these ratios to upper management, the management accountant would explain that each dollar invested in the Eastern Division generates $1.25 in sales revenues and each dollar of sales contributes $0.20 in profits. For the Western Division, each dollar invested generates only $0.80 in sales, although this division also yields $0.20 in profits from each dollar of sales. Obviously, the Eastern Division uses its assets more effectively, resulting in an ROI of 25 percent compared to the Western Division's ROI of 16 percent.

These ratios help focus managerial attention on the areas where ROI can be improved. Should the investment center manager look first to the income statement for operating improvements? An actual profit margin below the master budget profit margin signals this investigation. Should the manager look instead to the balance sheet for areas to improve in asset management? A lower than budget asset turnover ratio signals this course of action. Areas of investigation are summarized in Exhibit 20-19. To improve profits on sales, the manager might investigate whether the sales prices for products are set too low. Maybe the sales mix contained too many products with low CM ratios. If there are no problems with sales price and mix, the managers should investigate costs and cost variances.

|

R0I = Profit margin x Asset turnover |

|

|

|

|

(Net income / Sales) x (Sales / Assets) |

|||

|

|

$100,000 |

x |

$500,000 |

|

Eastern Division ROI = |

$500,000 |

$400,000 |

|

|

|

= 20% X 1.25 times |

||

|

|

= 25% |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

$140,000 |

x |

$700,000 |

|

Western Division ROI = |

$700,000 |

$875,000 |

|

|

|

= 20% X 0.80 times |

||

|

|

= 16% |

|

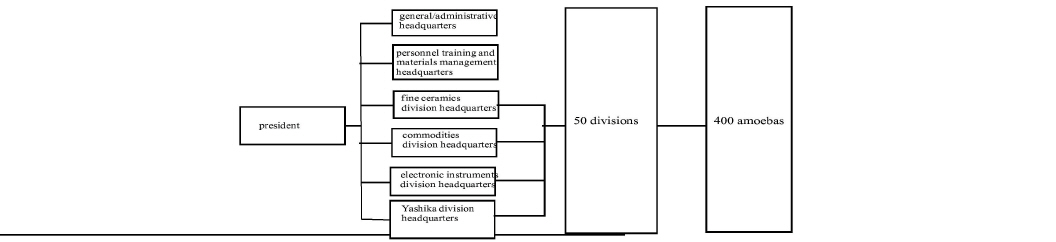

|