Anticipated Technological Change and Real Business

Cycles.David

R.F. Love and Jean-François Lamarche

Keywords: Anticipation, Real Business Cycles, Impulse Responses.

JEL: E10, E30, E37.

For example, changes in regulatory environments which are enacted through legislation are clearly anticipated well before they legally come into effect. California's zero-emissions-vehicle mandate is almost 10 years old and yet has two years remaining before automobile manufacturers will be forced to comply. Motorists in southern Ontario had between one and two years to prepare their vehicles for the provincial governments ``drive clean'' inspections. Dichloro-diphenyl-trichloro-ethane (DDT), leaded-gasoline, and chloro-flouro carbons (CFC's) are just three examples of products that were ``phased-out'' rather than being banned effective immediately. It is clear that this approach is the rule rather than the exception.

In terms of technological innovation, it is rare for the introduction of a new product or process to not be accompanied by a series of announcements and analyses. From colour television and the basics of silicon-chip technology in the late 1960's and early 1970's, to fiber optic cables, high speed internet access, cellular telephones, global positioning satellites, and fuel cells today, it is difficult to find an example of a new technology in which the readers of ``Popular Mechanics'' were not thoroughly versed, and which was not well anticipated by the public at large. Indeed the establishment of anticipation and hype for new ``revolutionary'' products is by now a standard marketing strategy. The timely releases of successive MicroSoft ``Windows'' operating systems and Intel ``Pentium'' chips provide ready examples.

This paper explores some of the implications of fully anticipated technological change for the predictions of real business cycle models.

Anticipation of technological change in our framework means that

economic

agents observe the outcome of a conventional stochastic technology

process

some ![]() periods prior to its impact on productivity. This is a simple variation

on the typical RBC methodology which is easy to handle within our

solution

algorithm for any

periods prior to its impact on productivity. This is a simple variation

on the typical RBC methodology which is easy to handle within our

solution

algorithm for any ![]() ,

where

,

where ![]() yields the standard unanticipated case. Conceptually then, a ``shock''

refers to the revelation of information about future productivities

rather

than to the impact of the productivity change itself. Note that this

opens

the possibility for negative productivity shocks, which are difficult

to

interpret within standard RBC frameworks, to be understood as downward

reassessments of the future productivity potential of technological

innovations.

yields the standard unanticipated case. Conceptually then, a ``shock''

refers to the revelation of information about future productivities

rather

than to the impact of the productivity change itself. Note that this

opens

the possibility for negative productivity shocks, which are difficult

to

interpret within standard RBC frameworks, to be understood as downward

reassessments of the future productivity potential of technological

innovations.

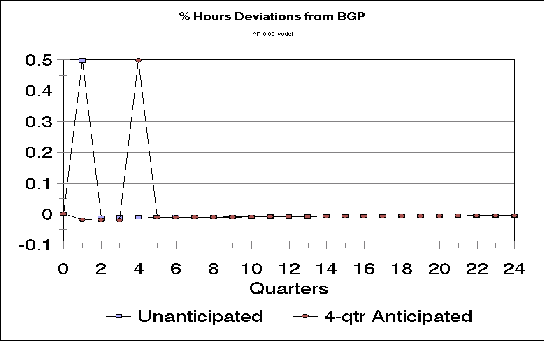

There are at least two basic ways in which anticipation as described above may have implications for the predictions of RBC models. First, allowing for agent's responses in anticipation of technological change may alter the model's predictions for the basic variances, and correlations of the economic variables central to most RBC theory. For example, anticipation of a future increase in factor productivity may alter agent's investment decisions. This may impact on measured investment volatility and could serve to reduce the correlation between investment and output. Also, agent's may substitute current leisure for anticipated increases in future consumption. This is the opposite labour-supply response to that seen when the technology actually arrives and thus may serve within the model to increase measured labour volatility.

Our simulation results confirm some of the above intuition. In general, for a given stochastic technology process, anticipation tends to raise the measured volatility of output, and the relative volatility of hours to output and investment to output. Additionally, anticipation effects break down the pattern of near perfect correlation between consumption, hours, and output which characterizes many RBC models.

Second, a period of anticipation prior to the impact of the technological change lengthens the possible response of the economy to any given shock. This has implications for the internal propagation properties of the model. As is well know (for example, Cogley and Nason, 1995) many RBC frameworks fail to generate output persistence or impulse responses that are consistent with actual data. Our simulation results show a dramatic effect of anticipation on estimates of impulse-response functions obtained from the model. In particular, when technological changes are anticipated, we estimate hump-shaped transitory response functions from our simulated data for output levels and hours which are similar to those obtained from US data, and where basically no response at all appears in the unanticipated case. These transitory dynamic responses in the presence of a period of anticipation are intuitive and are robust to several model specifications. In some cases strong autocorrelation of output growth is also predicted when technological changes are anticipated.

Our study is related to the interesting work of Beaudry and Portier (2000) who analyze a model where anticipation of technological change is based upon signals that are sometimes incorrect. Their emphasis, however, is on the potential recessionary effects of having (ex post) an overly optimistic view regarding the future path of technology in a model which differs from common RBC frameworks. Our work complements this by identifying the implications of correctly anticipating technological changes for a broad set of business-cycle predictions in common RBC models.

In the next section of the paper we outline a simple base-case RBC model and briefly discuss our simulation approach. Section 3 presents results from this model including estimation of impulse-response and autocorrelation functions from simulated data. In Section 4 we modify the base-case model assumptions for the stochastic technology process and relate impulse dynamics to the extent of anticipation effects. Section 5 extensively modifies the model to allow for endogenous growth and explores anticipation effects in several variants of that framework. Section 6 concludes.

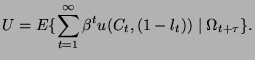

|

(1) |

![]() is period-t consumption, and

is period-t consumption, and ![]() is labour supplied from a unit endowment of time per period.

is labour supplied from a unit endowment of time per period. ![]() is the household's subjective rate of time preference. The period

utility

function is isoelastic over consumption and leisure and is

parameterized

as:

is the household's subjective rate of time preference. The period

utility

function is isoelastic over consumption and leisure and is

parameterized

as:

| (2) | |||

![]() ,

, ![]() denotes the household's time-t information set. If

denotes the household's time-t information set. If ![]() we have the standard RBC setup where the household has perfect

information

about the state of the economy up to and including the current period,

but future economic conditions are subject to uncertainty. Since this

situation

implies that, for example, variations in technologies are never

realized

in advance of the current decision making period, we refer to this as

the

unanticipated

case. Alternatively, if

we have the standard RBC setup where the household has perfect

information

about the state of the economy up to and including the current period,

but future economic conditions are subject to uncertainty. Since this

situation

implies that, for example, variations in technologies are never

realized

in advance of the current decision making period, we refer to this as

the

unanticipated

case. Alternatively, if ![]() ,

then the household's information set includes knowledge of the state of

the economy

,

then the household's information set includes knowledge of the state of

the economy![]() periods beyond the current decision making period, and we refer to this

as the

periods beyond the current decision making period, and we refer to this

as the ![]() -period

anticipated case.

-period

anticipated case.

The household's labour supply earns a competitive wage rate, ![]() .

Households also save directly in capital which is rented out each

period

for a competitive rate of return

.

Households also save directly in capital which is rented out each

period

for a competitive rate of return ![]() ,

and which follows the usual law of motion;

,

and which follows the usual law of motion; ![]() ,

where

,

where ![]() gives the rate of capital depreciation. The resulting household income

is allocated between consumption goods and capital investments implying

the following time-t budget constraint;

gives the rate of capital depreciation. The resulting household income

is allocated between consumption goods and capital investments implying

the following time-t budget constraint;

| (3) |

| (4) |

where, ![]() ,

and

,

and ![]() are standard production function coefficients.

are standard production function coefficients. ![]() is an exogenous productivity factor or ``technology shock'' process

assumed

to follow a random walk with drift such that;

is an exogenous productivity factor or ``technology shock'' process

assumed

to follow a random walk with drift such that;

| (5) |

The N-step forecast of this process conditional on ![]() is given by;

is given by;

| (6) |

with conditional variance;

| (7) |

The parameter ![]() was chosen to set capital's share of total income

was chosen to set capital's share of total income![]() equal to 0.35. The scale parameter

equal to 0.35. The scale parameter ![]() was normalized to unity. The depreciation rate

was normalized to unity. The depreciation rate ![]() was set at 2.4% per quarter.We set

was set at 2.4% per quarter.We set ![]() so that agent's subjective rate of time preference is 5% per year.We

choose

so that agent's subjective rate of time preference is 5% per year.We

choose ![]() in accordance with the average measure of hours worked from our data.

Since

this measure is of actual hours per week and the model normalizes

available

time to unity we must convert our data measure to percentage terms. Our

normalization assumes 16 discretionary hours available per day (112 per

week) and yields an average data value of 19.2%. This lies between the

17% specified in Jones et al. (2000) and the 24% employed by Gomme

(1993).

Our results are not sensitive within this range of values.

in accordance with the average measure of hours worked from our data.

Since

this measure is of actual hours per week and the model normalizes

available

time to unity we must convert our data measure to percentage terms. Our

normalization assumes 16 discretionary hours available per day (112 per

week) and yields an average data value of 19.2%. This lies between the

17% specified in Jones et al. (2000) and the 24% employed by Gomme

(1993).

Our results are not sensitive within this range of values.

Given selections for ![]() and

and ![]() ,

the choice of

,

the choice of ![]() is constrained by three factors. First, our preference specification

implies

an intertemporal elasticity of substitution given by

is constrained by three factors. First, our preference specification

implies

an intertemporal elasticity of substitution given by ![]() .

Evidence suggests that this should satisfy

.

Evidence suggests that this should satisfy ![]() (see,for example, Mehra and Prescott (1985)). Second, within this range

for the

(see,for example, Mehra and Prescott (1985)). Second, within this range

for the ![]() ,

too low a value of

,

too low a value of ![]() results in too high of a capital investment-to-output ratio

results in too high of a capital investment-to-output ratio ![]() which should lie roughly between 0.2 and 0.24. Third, too high a value

of

which should lie roughly between 0.2 and 0.24. Third, too high a value

of ![]() results in too high a real interest rate (inclusive of an equity

premium

the variance of real-rate estimates is huge but it seems clear that

anything

exceeding 10% would be unreasonable). Thus some compromise is

necessary.

We choose

results in too high a real interest rate (inclusive of an equity

premium

the variance of real-rate estimates is huge but it seems clear that

anything

exceeding 10% would be unreasonable). Thus some compromise is

necessary.

We choose ![]() to give reasonable values for all of these model variables in the

base-case.

to give reasonable values for all of these model variables in the

base-case.

In calibrating the stochastic technological process we choose ![]() to generate a quarterly balanced-growth rate of output

to generate a quarterly balanced-growth rate of output ![]() of 0.42% corresponding to the growth rate of U.S. GDP per worker in our

sampletypeset@protect @@footnote SF@gobble@opt We divide by the labour

force here rather than population to factor out increases in output

per-capita

due to the significant increases in participation rates over the

sample.

. As in Gomme (1993), and Beaudry and Portier (2000) we choose

of 0.42% corresponding to the growth rate of U.S. GDP per worker in our

sampletypeset@protect @@footnote SF@gobble@opt We divide by the labour

force here rather than population to factor out increases in output

per-capita

due to the significant increases in participation rates over the

sample.

. As in Gomme (1993), and Beaudry and Portier (2000) we choose ![]() so as to closely replicate the variance of output growth per-capita of

0.0095 found in our data sample.

so as to closely replicate the variance of output growth per-capita of

0.0095 found in our data sample.

Anticipation raises the variance of output ![]() and of output growth

and of output growth ![]() in the model relative to the unanticipated case, implying that less

exogenous

volatility is required in the model to capture this feature of the

data.

The anticipation assumption reverses the predictions of the model in

regards

to the relative variance of consumption-to-output

in the model relative to the unanticipated case, implying that less

exogenous

volatility is required in the model to capture this feature of the

data.

The anticipation assumption reverses the predictions of the model in

regards

to the relative variance of consumption-to-output ![]() ,

and investment-to-output

,

and investment-to-output ![]() .

Under anticipation

.

Under anticipation![]() falls by more than one-half so the model now under predicts the data,

and

falls by more than one-half so the model now under predicts the data,

and ![]() more than doubles so the model now over predicts the data. Anticipation

more than triples the relative variance of hours-to-output

more than doubles so the model now over predicts the data. Anticipation

more than triples the relative variance of hours-to-output ![]() bringing the model's predictions much closer with a feature of the data

that has proven difficult to match in simple RBC frameworks.

Additionally,

the anticipation effect breaks down the pattern of near perfect

correlations

of consumption with output

bringing the model's predictions much closer with a feature of the data

that has proven difficult to match in simple RBC frameworks.

Additionally,

the anticipation effect breaks down the pattern of near perfect

correlations

of consumption with output ![]() ,

investment with output

,

investment with output ![]() ,

and hours with output

,

and hours with output ![]() that characterizes many RBC models. This is particularly true for

that characterizes many RBC models. This is particularly true for ![]() which now significantly under estimates the data. Lastly, while all of

the predictions for the first-order autocorrelation of output

growth

which now significantly under estimates the data. Lastly, while all of

the predictions for the first-order autocorrelation of output

growth ![]() ,

and of consumption growth

,

and of consumption growth ![]() ,

are very close to zero, the small negative values predicted under the

anticipation

assumption indicate a worsening.

,

are very close to zero, the small negative values predicted under the

anticipation

assumption indicate a worsening.

Thus, the above results are mixed in terms of which model better fits these aspects of the data. It seems reasonable, however, to argue that the real world is not characterized by either extreme of only anticipated technological changes nor only unanticipated changes. This argument, together with the above results, suggests that anticipation effects are an important consideration in our understanding of business cycle phenomena and that an appropriately generalized model encompassing both possibilities could generate a set of intermediate predictions that are overall more closely in line with the evidence.

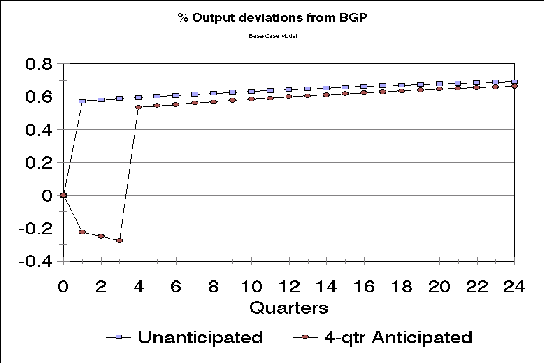

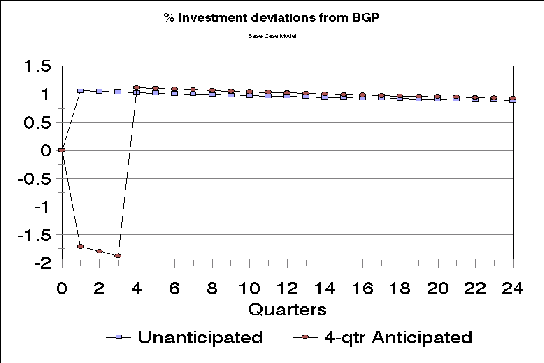

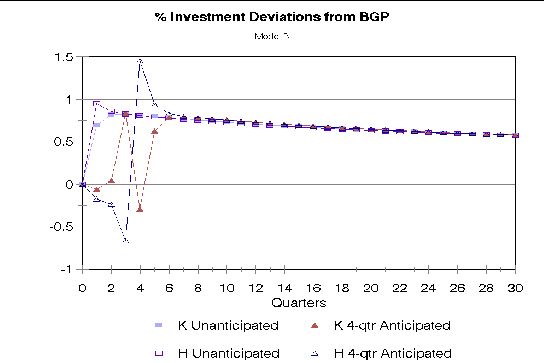

Figure 3 shows a

positive

anticipation effect in consumption. Again, this is due to intertemporal

substitution in anticipation of relatively high consumption in the

future.

As seen in Figure 4 it is

accomplished,

despite lower output over the anticipation period, by reductions in the

rate of investment. Since consumption rises during the period of

anticipation

while output falls, a lower correlation between these two variables

results

and, the relatively smooth path of consumption compared to output

implies

a lower ratio of standard deviations, ![]() .

.

As discussed by Beaudry and Portier (2000) the pattern of variable movements outlined above in response to an anticipated increase in technology is an artifact of the standard RBC model structure employed here. While it is tempting to relate the declines in hours, output, and investment with a recession (in the absence of technological regress), the co-movement of consumption with these variables distinctly contradicts the pattern observed in actual recessions. Clearly anticipation effects cannot make a fully comprehensive model of the business cycle out of the standard RBC structure, and it is not our objective here to argue that. However, as we will see further in the next section, anticipation effects in these models are significant and can address some of their other failures.

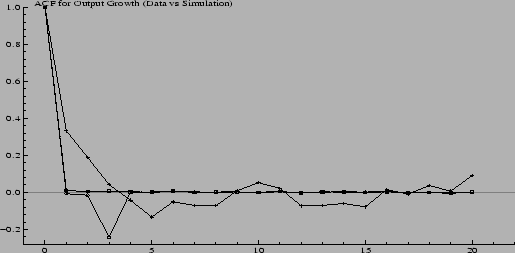

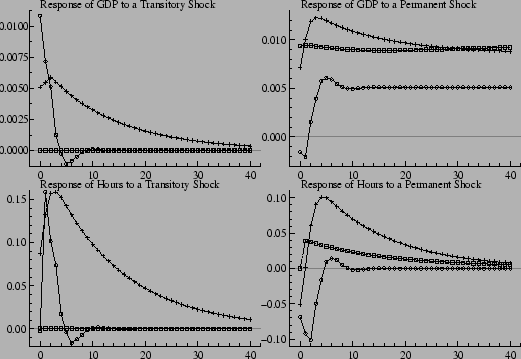

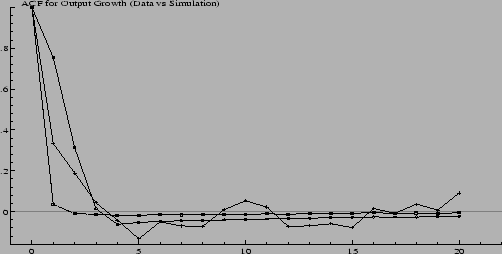

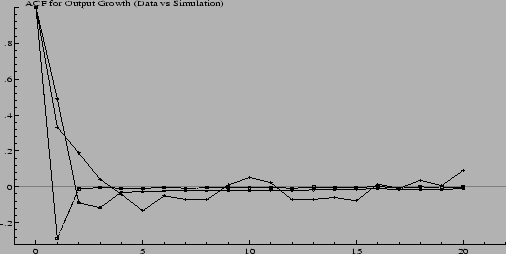

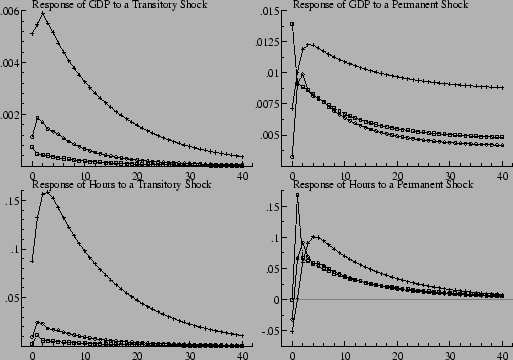

Impulse response functions are estimated employing the methodology of Blanchard and Quah (1989). Given an estimated bivariate autoregressive process obtained from stationary time-series (here quarterly per-capita output growth and hours), this methodology allows for the decomposition of the two variable's responses to shocks into transitory components, which by construction eventually die out, and permanent ones which need not.

Both in the data and in the simulations we use 187 observations

corresponding

to our sample period of 1954:1 to 2000:3. Estimates reported for the

model

simulations are the average over the number of replications ![]() .

In all cases we employ a lag length of 8.

.

In all cases we employ a lag length of 8.

Graphical visualisation of the autocorrelation functions and impulse

response functions is informative but we also report two statistics for

the autocorrelation. The first ![]() due to Gregory and Smith (1991) gives the probability of observing a

first-order

autocorrelation coefficient of output growth in the model that is at

least

as large as that found in the data.

due to Gregory and Smith (1991) gives the probability of observing a

first-order

autocorrelation coefficient of output growth in the model that is at

least

as large as that found in the data.

The second ![]() is discussed by Cogley and Nason (1995). The null hypothesis is that

the

simulated autocorrelation function is equal to the sample

autocorrelation

function and thus a low enough

is discussed by Cogley and Nason (1995). The null hypothesis is that

the

simulated autocorrelation function is equal to the sample

autocorrelation

function and thus a low enough ![]() -value

indicates that the model's autocorrelation function is not a good

approximation

to the sample autocorrelation functiontypeset@protect @@footnote

SF@gobble@opt

Further discussion regarding calculation of this statistic is provided

in the Appendix C. .

-value

indicates that the model's autocorrelation function is not a good

approximation

to the sample autocorrelation functiontypeset@protect @@footnote

SF@gobble@opt

Further discussion regarding calculation of this statistic is provided

in the Appendix C. .

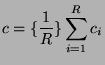

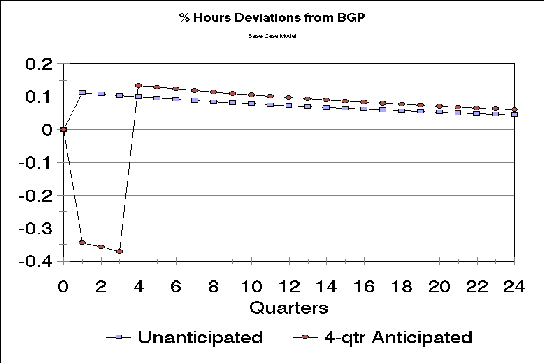

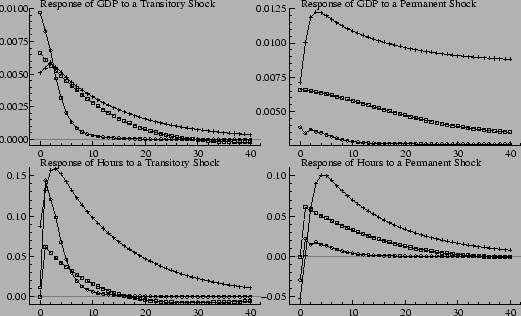

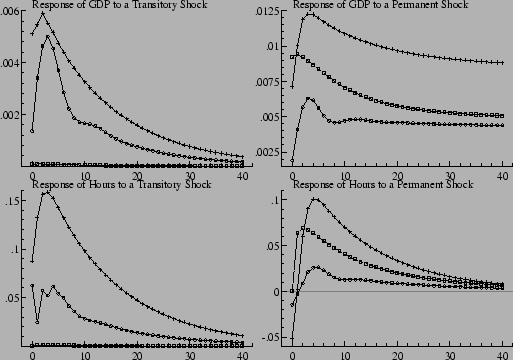

Figure 6 plots the impulse-response functions for output (GDP) and Hours estimated from the data and again, from the unanticipated, and 4-quarter anticipated simulations of our base-case model. As is well known (see, for example, Blanchard and Quah (1989)) the data for both GDP and hours show significant transitory and permanent responses to a shock. Further, each of these responses is characteristically ``hump-shaped''. These facts have proven difficult to replicate with standard RBC models (Cogley and Nason (1995)) and, as shown in Figure 6, the results for our unanticipated case continue to reflect this. The unanticipated case produces virtually no transitory response in either output or hours with the plotted function estimates lying almost entirely along the horizontal axis. While this case does generate permanent responses to a shock these are relatively small and essentially monotonic rather than hump-shaped as for the data.

The 4-quarter anticipated case, on the other hand, displays marked transitory responses in both output and hours. These estimated responses clearly differ from those obtained with the data, nonetheless they indicate an important trend-reverting component in modelled output and hours. Given these sizable transitory responses in the anticipated case, it is not surprising that the decomposition technique employed estimates smaller corresponding permanent responses than found for the unanticipated case. In favourable contrast to the unanticipated case, however, the permanent response functions for the anticipated case are distinctly hump-shaped as is consistent with the non-monotonic permanent responses estimated from the data.

Finally, note that the anticipated case also generates an initial negative response in the permanent hours function which is consistent with the data. This reflects the initial negative response of hours to anticipated future changes in productivity as seen in Figure 1 above. In general, the transitory responses seen when changes in technology are assumed to be anticipated are a reflection of the anticipation effects previously stylized in Figures 1 to 4, which are by their nature short-lived.

The production function specification in the model is modified to the following;

| (8) |

As before ![]() is a random productivity shock but is now specified astypeset@protect

@@footnote

SF@gobble@opt This specification for the shock process is adopted from

Jones, Manuelli, and Siu (2000). ;

is a random productivity shock but is now specified astypeset@protect

@@footnote

SF@gobble@opt This specification for the shock process is adopted from

Jones, Manuelli, and Siu (2000). ;

| (9) |

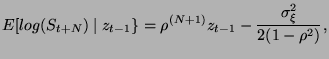

The N-step forecast of this stochastic process conditional on ![]() is given by,

is given by,

|

(10) |

with conditional variance of,

![$\displaystyle Var[log(S_{t+N})\mid z_{t-1}]=\sigma _{\xi }^{2}\sum ^{N}_{i=0}\rho ^{2i}.$](img70.png) |

(11) |

These assumptions imply that ![]() and the model has a well defined BGP. Further, for small

and the model has a well defined BGP. Further, for small![]() and in the limit as

and in the limit as ![]() this model is equivalent to that presented in Section 2

above where we assumed a random walk with drift. Essentially then this

model specification enables us to study the implications of the degree

of persistence in productivity shocks for our results. Also, for

this model is equivalent to that presented in Section 2

above where we assumed a random walk with drift. Essentially then this

model specification enables us to study the implications of the degree

of persistence in productivity shocks for our results. Also, for ![]() ,

productivity shocks are by definition temporary (although potentially

very

long-lived) relative to the exogenous growth path implied by the

evolution

of the scale parameter

,

productivity shocks are by definition temporary (although potentially

very

long-lived) relative to the exogenous growth path implied by the

evolution

of the scale parameter ![]() .

There are important implications of this for estimated transitory

responses

to shocks in the model where, based upon our earlier results, we may

expect

to see significant effects of anticipation and thus this specification

provides emphasis for this point of comparison.

.

There are important implications of this for estimated transitory

responses

to shocks in the model where, based upon our earlier results, we may

expect

to see significant effects of anticipation and thus this specification

provides emphasis for this point of comparison.

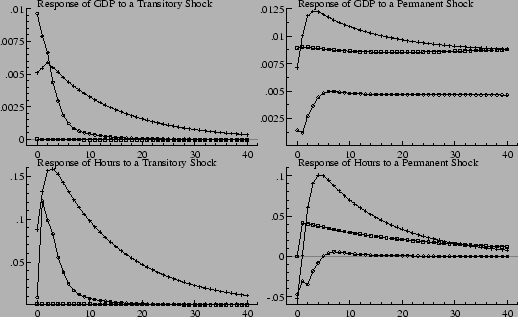

As should be expected the model results for the ![]() case are almost the same as those for the random walk model presented

in

Section 2 above. As the level of

persistence

in the shock process diminishes, however, it is apparent that the

differences

between the unanticipated results and the anticipated results narrows.

This effect is consistent across every statistic calculated and

continues

until, for the

case are almost the same as those for the random walk model presented

in

Section 2 above. As the level of

persistence

in the shock process diminishes, however, it is apparent that the

differences

between the unanticipated results and the anticipated results narrows.

This effect is consistent across every statistic calculated and

continues

until, for the ![]() case, there is virtually no difference between the unanticipated and

anticipated

cases.

case, there is virtually no difference between the unanticipated and

anticipated

cases.

The intuition for this result is quite simple. Agent's response in

anticipation

of future productivity changes is larger the longer lasting the effects

of those changes are expected to be. For short-lived changes there is

little

opportunity to benefit from intertemporal substitution of, for example,

labour supply and thus little response in anticipation of the change.

This

can be seen clearly by observing model impulse response functions.

Figure

7

displays, for the ![]() model, the percentage deviations of hours from a deterministic BGP in

both

the unanticipated and 4-quarter anticipated cases given a positive 1/2

percent productivity shock. Compared to Figure 1

from the earlier random walk model, it is clear how both the

anticipation

effect and the length of response subsequent to the shock vary with the

shock persistence. In the

model, the percentage deviations of hours from a deterministic BGP in

both

the unanticipated and 4-quarter anticipated cases given a positive 1/2

percent productivity shock. Compared to Figure 1

from the earlier random walk model, it is clear how both the

anticipation

effect and the length of response subsequent to the shock vary with the

shock persistence. In the ![]() model, the dominant distinguishing feature between the anticipated and

unanticipated cases is the timing of the arrival of the productivity

change,

and it is apparent how these two cases would be virtually

indistinguishable

statistically. Similar results are also apparent in regards to output,

consumption, and investment responses.

model, the dominant distinguishing feature between the anticipated and

unanticipated cases is the timing of the arrival of the productivity

change,

and it is apparent how these two cases would be virtually

indistinguishable

statistically. Similar results are also apparent in regards to output,

consumption, and investment responses.

The basic intuition above regarding the implications of persistence

for the effects of anticipation in the model extends to the estimated

impulse

response functions. Figure 9

shows

clearly that the estimated response functions in the unanticipated and

anticipated cases are essentially the same when the shocks show no

persistence ![]() .

.

Finally, we do not present estimated autocorrelation functions for these models as there is virtually no change in results. The models all continue to fail miserably in this regard.

We have seen for exogenous growth models that allowing for anticipation of technology change tends to weaken their (admittedly limited) ability to generate positive persistence in growth rates. Also, our work suggests that the effects of anticipation, particularly with respect to estimated impulse response functions, are sensitive to the assumed growth process. Finally, it is intuitive that allowing for the possibility of intersectoral substitution, as well as for intertemporal substitution, in response to an anticipated technological change may be important for our understanding of business cycles. These factors, and the work of Jones et al. (2000) motivate the analysis in this section of the paper of the effects of anticipation in a two-sector endogenous growth framework.

We present here a basic outline of the central remaining features of the model ostensibly for the purposes of establishing notation and a framework for further discussion. Proofs of the existence and uniqueness of competitive equilibrium in this framework, detailed analyses of balanced-growth solutions, and analytical characterizations of the model's transitional dynamic properties are well established elsewhere in the literature. An excellent reference in this regard for readers further interested is Barro and Sala-i-Martin (1996, chpt. 4).

We assume the same utility and information structure for the

representative

household as given in Section 2.1

above. Time available for leisure ![]() ,

however, is now subject to the following constraint;

,

however, is now subject to the following constraint;

| (12) |

where total hours available have been normalized to unity. ![]() represents hours supplied for employment in the final-goods sector,

and

represents hours supplied for employment in the final-goods sector,

and ![]() is hours employed in human-capital formation.

is hours employed in human-capital formation.

The household's effective labour supply ![]() earns a competitive wage rate,

earns a competitive wage rate, ![]() .

Households also save directly in physical capital which is rented out

each

period for a competitive rate of return,

.

Households also save directly in physical capital which is rented out

each

period for a competitive rate of return, ![]() .

The resulting household income is allocated between the purchase of

consumption

goods, physical-capital investments, and human-capital

accumulationtypeset@protect

@@footnote SF@gobble@opt The assumption that human-capital is

explicitly

purchased in a market rather than, say being produced by households at

home, is made for simplicity of exposition only. Under constant returns

to scale and perfect competition as assumed here, the results are

invariant

to this choice. implying the following time-t budget constraint;

.

The resulting household income is allocated between the purchase of

consumption

goods, physical-capital investments, and human-capital

accumulationtypeset@protect

@@footnote SF@gobble@opt The assumption that human-capital is

explicitly

purchased in a market rather than, say being produced by households at

home, is made for simplicity of exposition only. Under constant returns

to scale and perfect competition as assumed here, the results are

invariant

to this choice. implying the following time-t budget constraint;

| (13) |

Here ![]() ,

and

,

and ![]() give the rates of depreciation of physical-capital and human-capital

respectively,

and

give the rates of depreciation of physical-capital and human-capital

respectively,

and![]() gives the relative price of human capital in terms of final-goods.

gives the relative price of human capital in terms of final-goods.

Final-goods production, ![]() ,

is undertaken by firms which employ effective labour and rent

proportion

,

is undertaken by firms which employ effective labour and rent

proportion ![]() of the capital stock to maximize period-by-period profits. Human

capital

production,

of the capital stock to maximize period-by-period profits. Human

capital

production, ![]() ,

employs a symmetric production technology and pays the same wages and

rental

rates as in the final-goods sector. The corresponding production

technologies

are;

,

employs a symmetric production technology and pays the same wages and

rental

rates as in the final-goods sector. The corresponding production

technologies

are;

| (14) |

| (15) |

Here, ![]() ,

, ![]() ,

, ![]() ,

and

,

and ![]() are standard production function coefficients.

are standard production function coefficients. ![]() and

and ![]() are exogenous productivity shocks. For simplicity we will assume that

the

two sectors are subject to identical shocks in each period so that

are exogenous productivity shocks. For simplicity we will assume that

the

two sectors are subject to identical shocks in each period so that ![]() .

These shocks are assumed to follow the process given by Equations 9

to 11 in Section 4.1

abovetypeset@protect @@footnote SF@gobble@opt Note that, as opposed to

the model of Section 4.1,

the rate of growth here is a function of the scale parameters in the

constant

returns to scale production technologies (i.e.

.

These shocks are assumed to follow the process given by Equations 9

to 11 in Section 4.1

abovetypeset@protect @@footnote SF@gobble@opt Note that, as opposed to

the model of Section 4.1,

the rate of growth here is a function of the scale parameters in the

constant

returns to scale production technologies (i.e. ![]() and

and ![]() ).

In this version of the model therefore, similarly to the random walk

model

of Section 2, shocks will by

definition

have permanent effects. .

).

In this version of the model therefore, similarly to the random walk

model

of Section 2, shocks will by

definition

have permanent effects. .

The final-goods market-clearing condition is;

| (16) |

Market clearing in human-capital implies;

| (17) |

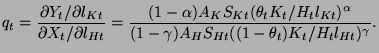

Finally, it can be readily shown that the optimal intersectoral allocation of factors implies the following expression for the relative price of human-capital in terms of final-goods output;

|

(18) |

Employing this condition we calculate aggregate economic output from the model as;

| (19) |

In order to isolate the effects of alternative parameter

specifications

and/or approaches to measurement on our results we adopt a

three-pronged

strategy. First we specify a base-case EGM model following a common

practice

in this framework of assuming perfect symmetry between production

sectors

(i.e. identical technologies (![]() and

and ![]() ),

and depreciation rates (

),

and depreciation rates (![]() )).

This amounts to assuming a single-sector model of homogeneous

output

)).

This amounts to assuming a single-sector model of homogeneous

output ![]() and consumption goods which therefore, relative to the models of

Sections

2

and 4 above, differs essentially

only

in regards to the endogenous versus exogenous growth assumption.

and consumption goods which therefore, relative to the models of

Sections

2

and 4 above, differs essentially

only

in regards to the endogenous versus exogenous growth assumption.

Second, in the perfectly symmetric sectors EGM the critical ratio of

human-to-physical capital is a constant and transitional dynamic

responses

of the capital stocks to changes in economic conditions transpire

within

a single time period. Assuming symmetric effects of technology changes

between sectors ![]() ,

this implies no intersectoral shifting of resources in response to any

given productivity shock, and thus rules out this possible avenue for

the

effects of anticipation of shocks. We therefore modify the base-case

EGM

to allow for alternative asymmetries between sectors and examine the

implications.

,

this implies no intersectoral shifting of resources in response to any

given productivity shock, and thus rules out this possible avenue for

the

effects of anticipation of shocks. We therefore modify the base-case

EGM

to allow for alternative asymmetries between sectors and examine the

implications.

Third we extend the base-case EGM and the asymmetric-sectors models in an attempt to address some of the measurement issues outlined above.

In each case calibration employs the same stylized facts and basic methodology used for the previous models. The specifics of each of these alternative approaches are discussed below in conjunction with the presentation of corresponding results.

Qualitatively the results here are perfectly analogous to those

found

for the base-case one-sector model studied above. Anticipation raises

the

variance of output ![]() and of output growth

and of output growth ![]() .

. ![]() falls while

falls while ![]() and

and ![]() increase under anticipation. The anticipation effect continues to break

down the pattern of near perfect correlations of consumption with

output

increase under anticipation. The anticipation effect continues to break

down the pattern of near perfect correlations of consumption with

output ![]() ,

investment with output

,

investment with output ![]() ,

and hours with output

,

and hours with output ![]() .

Lastly, anticipation worsens the model's already weak predictions

regarding

the first-order autocorrelations of output growth

.

Lastly, anticipation worsens the model's already weak predictions

regarding

the first-order autocorrelations of output growth ![]() ,

and of consumption growth

,

and of consumption growth ![]() .

Model impulse response functions for this base-case EGM are also

qualitatively

identical to those in Figures 1

to 4 from the one-sector

models

showing the same intuition as was discussed in that case.

.

Model impulse response functions for this base-case EGM are also

qualitatively

identical to those in Figures 1

to 4 from the one-sector

models

showing the same intuition as was discussed in that case.

Quantitatively, however, these effects are smaller than in the one-sector random walk model and can be seen to diminish with the degree of persistence in the shock process. The base-case EGM clearly shows the same effects of persistence as were seen for the alternative specifications of the one-sector model studied in Section 4 above.

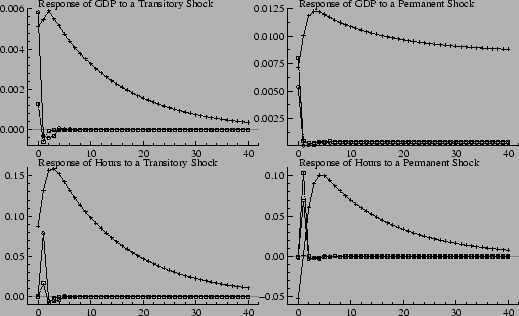

This fact is reiterated in the estimated impulse-response functions

for the model shown in Figure 10

for the ![]() case, and Figure 11

for the

case, and Figure 11

for the ![]() case. As for the one-sector model the base-case EGM shows no transitory

responses of either hours or output, but significant transitory

responses

are estimated in the anticipated case. Correspondingly, permanent

responses

are estimated to be smaller under anticipation. These estimated impulse

response functions are very similar in the

case. As for the one-sector model the base-case EGM shows no transitory

responses of either hours or output, but significant transitory

responses

are estimated in the anticipated case. Correspondingly, permanent

responses

are estimated to be smaller under anticipation. These estimated impulse

response functions are very similar in the ![]() case to those for the base-case one-sector model where shocks followed

a random walk and, in particular, they show a characteristic

hump-shaped

response. This later property is lost, however, as the shock

persistence

declines. A comparison with the

case to those for the base-case one-sector model where shocks followed

a random walk and, in particular, they show a characteristic

hump-shaped

response. This later property is lost, however, as the shock

persistence

declines. A comparison with the ![]() case shows reduced responses on the transitory side under anticipation,

and permanent responses under anticipation which are getting closer to

the of responses seen in the unanticipated case.

case shows reduced responses on the transitory side under anticipation,

and permanent responses under anticipation which are getting closer to

the of responses seen in the unanticipated case.

These results indicate that endogenizing the growth process in itself has little impact on the nature of the effects of anticipation of productivity shocks for the business cycle predictions of this class of models.

In the first of these alternatives (EGM-B) we reduce the intensity

of

physical-capital utilization in the human-capital sector (smaller ![]() )

by a small margin such that the estimated income share of capital in

GDP

(and by construction also the share of labour) continues to satisfy the

calibration requirements. In the second alternative (EGM-C) we reduce

the

rate of depreciation on human capital relative to the rate on physical

capital. In both of these cases we fix

)

by a small margin such that the estimated income share of capital in

GDP

(and by construction also the share of labour) continues to satisfy the

calibration requirements. In the second alternative (EGM-C) we reduce

the

rate of depreciation on human capital relative to the rate on physical

capital. In both of these cases we fix ![]() .

The corresponding calibrations for these models are given in Tables 8

and 9 found in Appendix D.

.

The corresponding calibrations for these models are given in Tables 8

and 9 found in Appendix D.

Table 6 presents the

corresponding

RBC statistics estimated from our simulated data. Generally,

anticipation

of technology change continues to have significant effects. Except

where

investment is concerned we once again find the same basic pattern of

results

as for our previous models. In the EGM-B case ![]() is still seen to rise with anticipation, however, in the EGM-C case

there

is a significant fall in this measure relative to the unanticipated

case.

In both the EGM-B and EGM-C cases we also see a dramatic fall, rather

than

only a minor one, in the correlation of investment to output

is still seen to rise with anticipation, however, in the EGM-C case

there

is a significant fall in this measure relative to the unanticipated

case.

In both the EGM-B and EGM-C cases we also see a dramatic fall, rather

than

only a minor one, in the correlation of investment to output![]() in the anticipated case relative to the unanticipated case.

in the anticipated case relative to the unanticipated case.

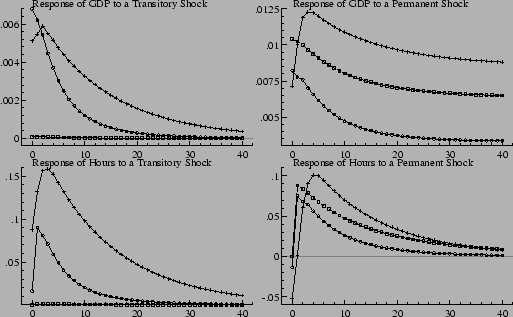

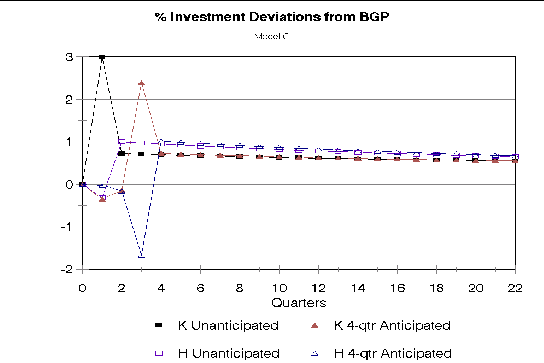

These results can be understood by observing the model impulse response functions. For hours, consumption, and output, these transition paths remain qualitatively identical to those shown for the base-case one-sector model in Figures 1 to 3 above. In these asymmetric sector models, however, since the ratio of human-to-physical capital is no longer constant, but varies in transition, the investment paths for human versus physical-capital, rather than being identical, show markedly different behaviours from each other. Figure 12, shows the paths of human and physical-capital investment in the EGM-B model in response to a 1/2 percent positive productivity shock. In the anticipated case physical-capital investment rises in the periods prior to the technological change, and falls significantly on the arrival date (period 4) before rising again subsequent to the technological change taking effect. Human-capital investment follows an opposite pattern. The movements of physical-capital investment at the arrival date are in the opposite direction to those for output on this date, and being relatively large, this accounts for the models low prediction regarding the correlation of output and physical-capital investment.

Figure 13 shows that investment deviations in the EGM-C model follow similar paths, although with generally higher volatility than in the EGM-B case which accounts for the increased relative volatility of investment to output in this model. Also, the timing of investment swings differs. This is a reflection of the asymmetries in depreciation rates between sectors which characterizes this model. In the anticipated case, while physical-capital investment is still high in the period before the arrival date, and human-capital investment is low, there is no overshooting of these rates from their long-run levels on the arrival date itself. The transitional responses of investments are essentially completed before the arrival date. This is contrasted with the unanticipated case, where the need to adjust the ratio of capital stocks in response to the arrival of the technological shock forces adjustment on the arrival date itself and accounts for the reduction in the relative volatility of physical-capital investment to output under anticipation.

Finally, estimated impulse-response and autocorrelation functions for these asymmetric cases show almost no variation in results relative to the symmetric sector model and thus are not presented here. There does arise a very small estimated transitory response for both output and hours in the unanticipated cases which verifies the intuition that allowing for intersectoral reallocations of resources in response to shocks may influence the models output dynamics, however, there are no implications for the relative effects of anticipation.

To account for this we adjust our measures of output and

incomes

earned from the human-capital sector by fraction ![]() .

These adjustments have no impact on the actual structure of the model

(aside

from a need for re-calibration) but only affect how our simulated data

series are constructed from the model solutions.

.

These adjustments have no impact on the actual structure of the model

(aside

from a need for re-calibration) but only affect how our simulated data

series are constructed from the model solutions.

Since some fraction of labour inputs to the human-capital production process are not measured (for example, student hours in school, parental inputs, some portion of time learning-by-doing) we write,

| (20) |

These adjustments do not address the inclusion of human-capital investments in aggregate consumption data. In our view the least ad-hoc method of dealing with this expenditure side measurement issue would be to subtract from the actual consumption data those components which are readily attributed to human-capital accumulation. To this end we deducted personal consumption expenditures on education and research services, and personal consumption expenditures on medical services from our base consumption series for the U.S. We found no appreciable difference in the statistical properties of this series over the base consumption series (besides the reduction in average percentage of GDP) and thus do not report particular results in this regard.

The modification of our models to account for these measurement

changes

requires alternative calibrations in order to continue to provide

variable

solutions consistent with observation. By assuming that more hours are

actually worked in human-capital accumulation than are measured, total

hours in the model must rise for measured hours to match our

calibration

requirements. The percentage of human-capital output in measured

aggregate

output falls by roughly one half from 40% of measured aggregate output

to 20%, which seems like a more reasonable number. Since

physical-capital

investment is fully measured in the model, but the measure of aggregate

output is now smaller, the ![]() ratio falls unless depreciation rates are lowered.

ratio falls unless depreciation rates are lowered.

We refer to these variations of our model as the ``unmeasured'' cases (``Base-Case EGMu'', ``EGMu-B'', ``EGMu-C''). The parameters and balanced-growth variable values for each of these calibrations are given in Tables 10, 11, and 12 found in Appendix D.

In regards to the asymmetric sector cases there are three basic results. First, volatilities of output, and output growth tend to fall with anticipation here rather than rise as we saw in the earlier results. Second, incomplete measurement of the human-capital sector further exacerbates the breakdown in the near perfect correlations between output and consumption, output and investment, and output and hours which results in the anticipated cases. Finally, the ``EGMu-B'' and ``EGMu-C'' cases both show substantial positive autocorrelation of output growth for the case of anticipated technological change. As might be expected then, and as is shown in the next section, these cases also improve significantly on the models predictions for the autocorrelation function of output growth.

Of course the models fail on some dimensions. Estimated autocorrelation functions are consistently rejected by our calculated Q-statistics relative to the sample functions for example. But the central point, that anticipation is important for the predictions of these models remains valid and we see no reason why this should not extend to other alternative frameworks. Intuitively, actual economies are likely characterized by combinations of anticipated and unanticipated change as well as processes of updating expectations of change with the revelation of new information. We see this as a promising avenue for future research in the RBC literature and elsewhere.

Appendix A. Data.

U.S. quarterly data series employed covered the period 1954:1 to 2000:3. Series denoted in italics where obtained from the National Income and Product Accounts data matrix (NIPAQ) downloaded from the EconData web-site at the University of Maryland. Series denoted in noun-style type where obtained from the Federal Reserve Economic Database (FRED) and where aggregated from monthly to quarterly. Where applicable all series were deflated by the implicit price deflator (d0104), and were divided by the civilian non-institutional population 16 years of age and older (CNP16OV) to obtain per-capita values.

Output figures are gross domestic product (n0101).

Consumption is measured as the sum of, personal consumption expenditure (c0201), Federal government defense expenditures (g0704), Federal government non-defense expenditures (g0715), and State and Local government expenditures (g0728).

Labour income was measured as the sum of, compensation of employees (n1402) and proprietors income with inventory valuation and capital consumption adjustments (n1409).

Capital income was measured as gross national income (n0928) less labour income.

Capital investment was measured by the sum of, private fixed investment (v0401), Federal government defense investment (g0711), Federal government non-defense investment (g0724), and State and Local government investment (g0735).

Our measure of ``hours worked'' accords closely with the Citibase

``Lhours''

series which was not used as it ends at the last month of 1993. Thus we

constructed;

where avg.hrs. was given by, average weekly hours of production workers (BLS national employment, hours, and earnings series EEU005 annual figures extrapolated to quarterly) for the period 1954:0 to 1963:4, and by average weekly hours of non-agricultural workers (awhnonag) for the period 1964:1 to 2000:3 (monthly data averaged to quarterly). The later series was employed as the former is seasonally unadjusted after 1964. In any case, all of our results appear robust to this choice. Employment was measured by civilian employment 16 years of age and older (CE16OV), and population was again (CNP16OV).

Finally, the labour force was measured by the civilian labour force 16 years of age and older (CLF16OV).

Appendix B. Numerical Simulation.

At the beginning of any time period t, the economy's initial

conditions

are predetermined by the current value of the state variable ![]() .

Also at the beginning of this period we assume that agent's realize the

time

.

Also at the beginning of this period we assume that agent's realize the

time ![]() outcome of the stochastic process

outcome of the stochastic process ![]() ,

for some

,

for some ![]() .

Equivalently, at each point in time we have an assumption of perfect

foresight

for the future period

.

Equivalently, at each point in time we have an assumption of perfect

foresight

for the future period ![]() ,

and the future sequence of technology variables is therefore known for

this sub-period. Technology variables for times

,

and the future sequence of technology variables is therefore known for

this sub-period. Technology variables for times![]() are forecast conditional on this information, and according to agents'

knowledge of the evolution of the stochastic process

are forecast conditional on this information, and according to agents'

knowledge of the evolution of the stochastic process![]() as given by equations 5 to 7.

as given by equations 5 to 7. ![]() gives the possibly infinite length of agents' forecast horizon. A

rational

expectations forecast for the entire future sequence of technology

variables

is thus made and a solution for the economy's optimal transitional

response

in light of this sequence can be calculated by employing standard

methodstypeset@protect

@@footnote SF@gobble@opt We employ a two-point boundary solution method

based on exact specifications of the model's dynamic equations system.

As discussed by Fair and Taylor (1984), this imposes the model's

terminal

conditions improving the efficiency of the solution method. . This

expected

transition path yields observations for the time t choice variables of

the model which determine the time t+1 state variable values. These

state

variables in turn represent the time t+1 initial conditions for the

economy

when a new outcome of the stochastic process

gives the possibly infinite length of agents' forecast horizon. A

rational

expectations forecast for the entire future sequence of technology

variables

is thus made and a solution for the economy's optimal transitional

response

in light of this sequence can be calculated by employing standard

methodstypeset@protect

@@footnote SF@gobble@opt We employ a two-point boundary solution method

based on exact specifications of the model's dynamic equations system.

As discussed by Fair and Taylor (1984), this imposes the model's

terminal

conditions improving the efficiency of the solution method. . This

expected

transition path yields observations for the time t choice variables of

the model which determine the time t+1 state variable values. These

state

variables in turn represent the time t+1 initial conditions for the

economy

when a new outcome of the stochastic process ![]() is realized and thus the basis for a solution of the time t+1 expected

transition path is established.

is realized and thus the basis for a solution of the time t+1 expected

transition path is established.

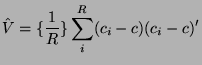

Iteration on the above process Q times yields a Q-period artificial time series for our model economy from which estimates of the moments of the model's variables can be obtained. Following a standard RBC approach (Prescott, 1986), we replicate this entire process R times to generate a large number of such artificial time series and a large sample of estimated moments the averages of which are then compared to real economic data.

In practice we set ![]() for the solution of each transition path. This is adequate to ensure

that

the model converges to its long run balanced growth path with a high

degree

of numerical accuracytypeset@protect @@footnote SF@gobble@opt Lower

values

would be adequate with lower persistence in the stochastic process, and

correspondingly larger values would be appropriate in the case of

greater

persistence. . We set Q=200 but truncate the first observations to

eliminate

any dependence of the simulated series on the

for the solution of each transition path. This is adequate to ensure

that

the model converges to its long run balanced growth path with a high

degree

of numerical accuracytypeset@protect @@footnote SF@gobble@opt Lower

values

would be adequate with lower persistence in the stochastic process, and

correspondingly larger values would be appropriate in the case of

greater

persistence. . We set Q=200 but truncate the first observations to

eliminate

any dependence of the simulated series on the ![]() starting values. This yields time-series of equal length to our actual

data sample (187 observations)typeset@protect @@footnote SF@gobble@opt

See Gregory and Smith (1991) for the statistical rational behind

requiring

equal sample sizes. . Finally we perform R=1000 replications for each

model

presented.

starting values. This yields time-series of equal length to our actual

data sample (187 observations)typeset@protect @@footnote SF@gobble@opt

See Gregory and Smith (1991) for the statistical rational behind

requiring

equal sample sizes. . Finally we perform R=1000 replications for each

model

presented.

Appendix C. ACF Statistic.

![]() is computed as,

is computed as,

This type of statistic can also be computed for the impulse-response

functions if the number of shocks in the model is as large as the order

of the vector autoregression (here, two). In the present paper,

however,

there is only one shock (applied symmetrically to both sectors in the

endogenous

growth model) and hence the ![]() statistics for the impulse-response functions are not available.

statistics for the impulse-response functions are not available.

| Model Parameters. |

| Balanced-Growth Variable Values |

| U.S. Data | Unanticipated | 4-qtr Anticipated | |

| 0.0095 | 0.0095 | 0.014 | |

| 1.62 | 1.21 | 1.61 | |

| 0.63 | 0.76 | 0.37 | |

| 2.34 | 1.85 | 3.91 | |

| 0.78 | 0.198 | 0.68 | |

| 0.85 | 0.998 | 0.58 | |

| 0.91 | 0.996 | 0.96 | |

| 0.87 | 0.982 | 0.93 | |

| 0.33 | 0.011 | -0.007 | |

| 0.16 | 0.03 | -0.003 |

Notation: ![]() gives the standard deviation of variable x.

gives the standard deviation of variable x. ![]() gives the correlation of variables

gives the correlation of variables ![]() and

and ![]() .

. ![]() gives the first-order autocorrelation of variable

gives the first-order autocorrelation of variable![]() .

. ![]() denotes aggregate output, and

denotes aggregate output, and ![]() its growth rate.

its growth rate.![]() denotes consumption, and

denotes consumption, and ![]() its growth rate.

its growth rate. ![]() denotes capital investment, and

denotes capital investment, and ![]() total hours.

total hours.

|

|

|

|

|

Quarters |

| Data | |||||||

| Un | An | Un | An | Un | An | ||

| 0.0095 | 0.0093 | 0.013 | 0.0098 | 0.012 | 0.0115 | 0.0116 | |

| 1.62 | 1.19 | 1.47 | 1.25 | 1.40 | 0.783 | 0.785 | |

| 0.63 | 0.64 | 0.35 | 0.48 | 0.31 | 0.24 | 0.23 | |

| 2.34 | 2.29 | 3.77 | 2.88 | 3.62 | 3.66 | 3.69 | |

| 0.78 | 0.3 | 0.65 | 0.44 | 0.61 | 0.619 | 0.623 | |

| 0.85 | 0.995 | 0.696 | 0.982 | 0.856 | 0.98 | 0.987 | |

| 0.91 | 0.995 | 0.972 | 0.99 | 0.987 | 0.999 | 0.999 | |

| 0.87 | 0.985 | 0.951 | 0.986 | 0.977 | 0.998 | 0.999 | |

| 0.33 | 0.0086 | -0.0087 | -0.012 | -0.023 | -0.491 | -0.492 | |

| 0.16 | 0.041 | 0.024 | 0.04 | 0.032 | -0.479 | -0.485 |

Notation: ![]() gives the standard deviation of variable x.

gives the standard deviation of variable x. ![]() gives the correlation of variables

gives the correlation of variables ![]() and

and ![]() .

. ![]() gives the first-order autocorrelation of variable

gives the first-order autocorrelation of variable![]() .

. ![]() denotes aggregate output, and

denotes aggregate output, and ![]() its growth rate.

its growth rate.![]() denotes consumption, and

denotes consumption, and ![]() its growth rate.

its growth rate. ![]() denotes capital investment, and

denotes capital investment, and ![]() total hours.

total hours.

|

Quarters |

Quarters |

| Model Parameters. |

| Balanced-Growth Variable Values |

| U.S. Data | case | case | |||

| Un | An | Un | An | ||

| 0.0095 | 0.0107 | 0.012 | 0.0092 | 0.012 | |

| 1.62 | 1.36 | 1.44 | 1.17 | 1.39 | |

| 0.63 | 0.52 | 0.42 | 0.73 | 0.46 | |

| 2.34 | 1.28 | 1.34 | 1.15 | 1.36 | |

| 0.78 | 0.398 | 0.49 | 0.22 | 0.53 | |

| 0.85 | 0.993 | 0.97 | 0.999 | 0.84 | |

| 0.91 | 0.999 | 0.999 | 0.999 | 0.994 | |

| 0.87 | 0.992 | 0.986 | 0.992 | 0.92 | |

| 0.33 | -0.012 | -0.015 | 0.012 | 0.003 | |

| 0.16 | 0.018 | 0.0084 | 0.13 | 0.004 |

Notation: ![]() gives the standard deviation of variable x.

gives the standard deviation of variable x. ![]() gives the correlation of variables

gives the correlation of variables ![]() and

and ![]() .

. ![]() gives the first-order autocorrelation of variable

gives the first-order autocorrelation of variable![]() .

. ![]() denotes aggregate output (equation 19

from the model), and

denotes aggregate output (equation 19

from the model), and ![]() its growth rate.

its growth rate. ![]() denotes final-goods consumption, and

denotes final-goods consumption, and ![]() its growth rate.

its growth rate. ![]() denotes physical-capital investment, and

denotes physical-capital investment, and ![]() total hours

total hours ![]() .

.

Quarters |

Quarters |

| Data | EGM-B | Case | EGM-C | Case | |

| Un | An | Un | An | ||

| 0.0095 | 0.0106 | 0.012 | 0.0109 | 0.012 | |

| 1.62 | 1.35 | 1.43 | 1.38 | 1.47 | |

| 0.63 | 0.52 | 0.42 | 0.49 | 0.40 | |

| 2.34 | 1.20 | 1.36 | 3.16 | 2.52 | |

| 0.78 | 0.40 | 0.49 | 0.41 | 0.5 | |

| 0.85 | 0.99 | 0.97 | 0.99 | 0.97 | |

| 0.91 | 0.99 | 0.19 | 0.67 | 0.047 | |

| 0.87 | 0.99 | 0.98 | 0.99 | 0.987 | |

| 0.33 | -0.015 | -0.02 | -0.007 | -0.016 | |

| 0.16 | 0.014 | -0.01 | 0.017 | 0.0026 |

Notation: ![]() gives the standard deviation of variable x.

gives the standard deviation of variable x. ![]() gives the correlation of variables

gives the correlation of variables ![]() and

and ![]() .

. ![]() gives the first-order autocorrelation of variable

gives the first-order autocorrelation of variable![]() .

. ![]() denotes aggregate output (equation 19

from the model), and

denotes aggregate output (equation 19

from the model), and ![]() its growth rate.

its growth rate. ![]() denotes final-goods consumption, and

denotes final-goods consumption, and ![]() its growth rate.

its growth rate. ![]() denotes physical-capital investment, and

denotes physical-capital investment, and ![]() total hours

total hours ![]() .

.

|

|

| Data | Base-Case | EGMu | ``EGMu-B''& case | ``EGMu-C''& case | |||

| Un | An | Un | An | Un | An | ||

| 0.0095 | 0.0097 | 0.104 | 0.0093 | 0.005 | 0.0015 | 0.0073 | |

| 1.62 | 1.247 | 1.28 | 1.22 | 1.04 | 1.453 | 1.168 | |

| 0.63 | 0.496 | 0.41 | 0.51 | 0.51 | 0.42 | 0.44 | |

| 2.34 | 1.68 | 1.8 | 1.56 | 3.43 | 3.54 | 3.64 | |

| 0.78 | 0.365 | 0.434 | 0.35 | 0.41 | 0.51 | 0.48 | |

| 0.85 | 0.99 | 0.97 | 0.99 | 0.92 | 0.942 | 0.91 | |

| 0.91 | 0.998 | 0.997 | 0.98 | 0.20 | 0.86 | 0.48 | |

| 0.87 | 0.994 | 0.987 | 0.99 | 0.80 | 0.945 | 0.87 | |

| 0.33 | -0.017 | -0.02 | 0.003 | 0.73 | -0.29 | 0.47 | |

| 0.16 | -0.006 | -0.004 | 0.004 | -0.02 | 0.006 | -0.006 |

Notation: ![]() gives the standard deviation of variable x.

gives the standard deviation of variable x. ![]() gives the correlation of variables

gives the correlation of variables ![]() and

and ![]() .

. ![]() gives the first-order autocorrelation of variable

gives the first-order autocorrelation of variable![]() .

. ![]() denotes aggregate output (equation 20

from the model), and

denotes aggregate output (equation 20

from the model), and ![]() its growth rate.

its growth rate. ![]() denotes final-goods consumption, and

denotes final-goods consumption, and ![]() its growth rate.

its growth rate. ![]() denotes physical-capital investment, and

denotes physical-capital investment, and ![]() total hours

total hours ![]() .

.

|

Quarters |

|

Quarters |

| Model Parameters |

| Balanced-Growth Variable Values |

| Model Parameters |

| Balanced-Growth Variable Values |

Appendix D, Continued.

| Model Parameters |

| Balanced-Growth Variable Values |

| Model Parameters |

| Balanced-Growth Variable Values |

| Model Parameters |

| Balanced Growth Variable Values |

Copyright © 1993, 1994, 1995, 1996,

Nikos

Drakos, Computer Based Learning Unit, University of Leeds.

Copyright © 1997, 1998, 1999,

Ross

Moore, Mathematics Department, Macquarie University, Sydney.

The command line arguments were:

latex2html -no_subdir -split 0 -show_section_numbers

/home/loved/Working/Papes/RBCgrow/RBCAnt-v3.tex

The translation was initiated by David Love on 2001-10-27